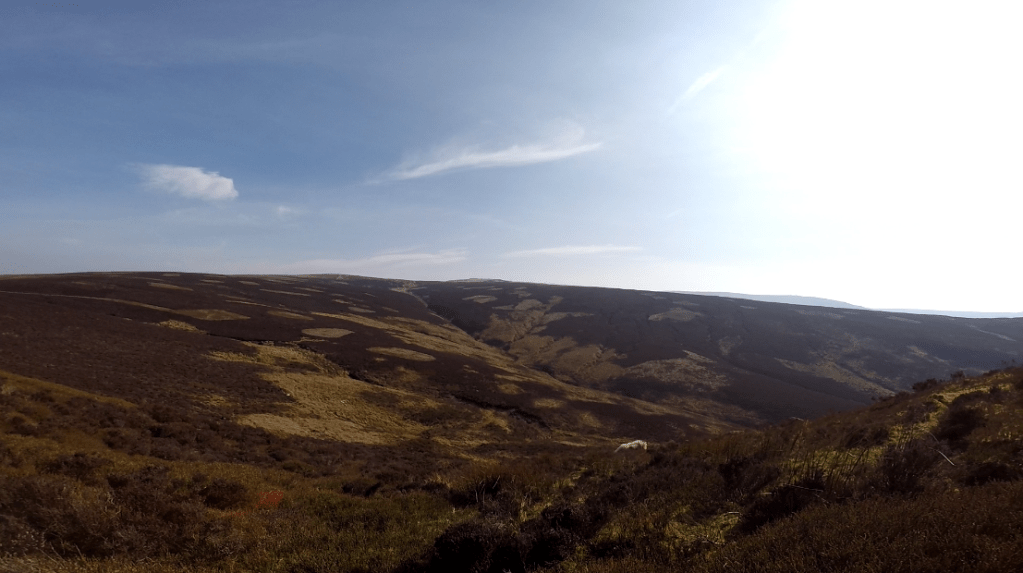

The National Trust’s (NT) grouse shooting policy in the Peak District National Park has featured a few times on this blog, most notably in 2016 when the National Trust terminated a grouse shooting lease four years before it was due to expire on the Hope Woodlands and Park Hall estates following allegations of illegal raptor persecution (here).

In a direct response to this event, in 2017 the NT modified its grouse shooting tenancy agreements (here) and brought in three new tenants under new, five-year leases.

In 2022, following the ‘disappearance’ of a breeding pair of hen harriers on a National Trust-leased moor in the Peak District (here), the NT came under more public pressure to stop leasing its moors to grouse-shooting tenants.

In 2023 it terminated another grouse shooting lease at Park Hall following more allegations of wildlife crime and announced that no further grouse shooting leases would be issued on this particular NT moor and that it would now be re-wilded (here).

In November 2023 I attended the Northern England Raptor Forum’s (NERF) annual conference in Barnsley.

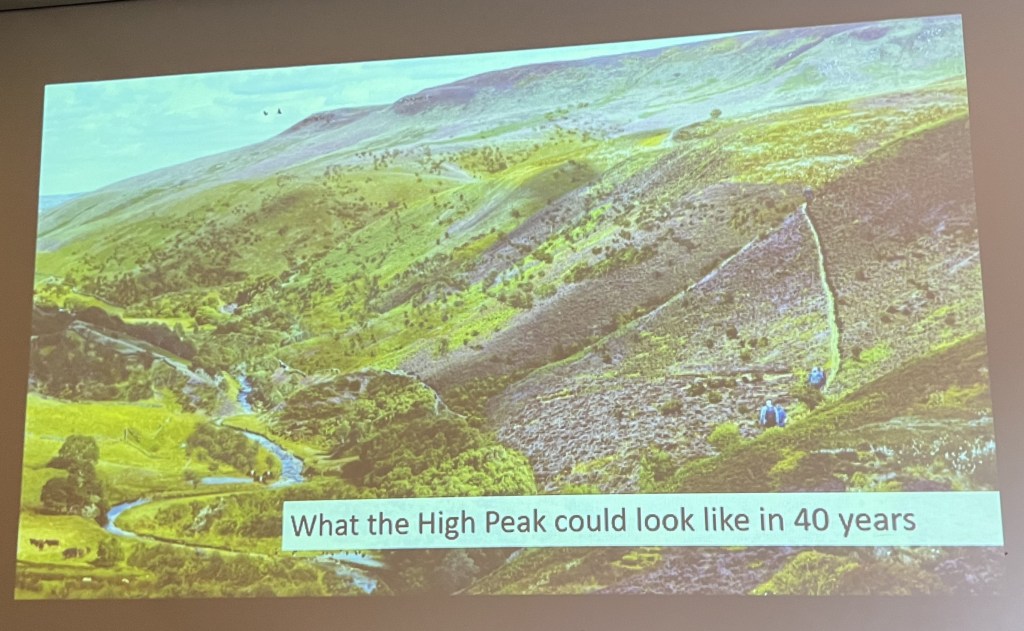

One of the presenters was Craig Best, the National Trust’s recently-appointed Peak District General Manager. Prior to taking this post in the Peak District, Craig had spent many years developing and overseeing the delivery of large scale moorland restoration and natural flood management on National Trust moorland in West Yorkshire. If you have an opportunity to hear him speak about his work, I recommend you do so. He’s knowledgeable, thoughtful and passionate about nature restoration.

At the NERF conference, Craig spoke about the National Trust’s vision for its Peak District moorlands and he alluded to various new elements of the NT’s game shooting policy.

I contacted the National Trust afterwards and asked if it had any written documents I could read about this new game shooting policy. Nick Collinson, the NT’s National Manager on Wildlife Management was kind enough to send me the following summary:

‘We facilitate a range of recreational activities on our land, and we recognise that for some people, shooting is an important part of rural heritage and the rural economy. It has a long history as a recreational activity in the countryside. We also appreciate that there are a range of views on game shooting, and we regularly engage with different groups and individuals who have an interest in the topic. In developing our approach we have spoken to both shooting and nature conservation organisations.

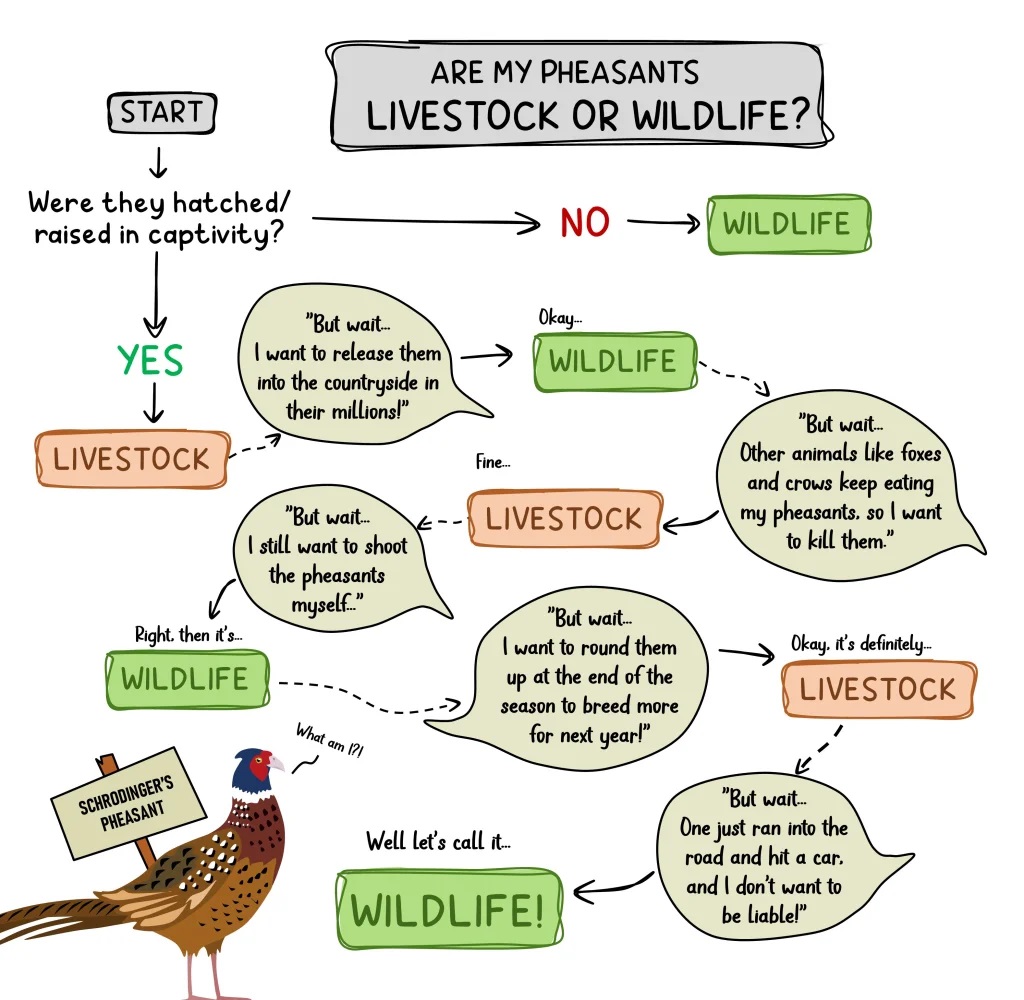

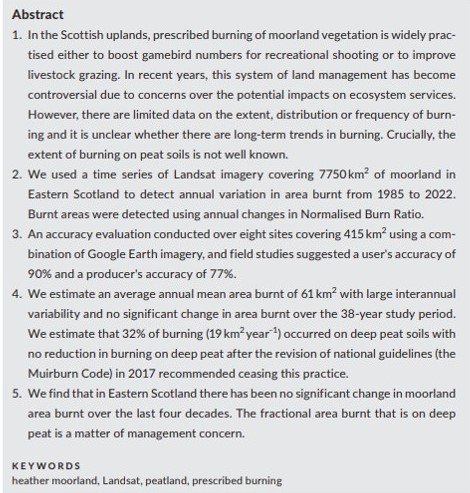

We will continue to consider the leasing of game shooting rights (red grouse, pheasant, red-legged partridge, and limited wildfowling, only), but only where the activity is compatible with our aims for the land, for restoring nature (e.g. we do not permit burning of moorland vegetation on peat soils), and for local access. We will therefore now only consider leases for low intensity shoots with low numbers of birds, which in many places should negate the need for predator control to sustain high numbers of game birds. All shoots must comply with the terms of their lease, the Code of Good Shooting Practice, and the law, and to support this, all shoots will be required to develop a Shoot Plan which will set out, and work through, shoot and National Trust objectives.

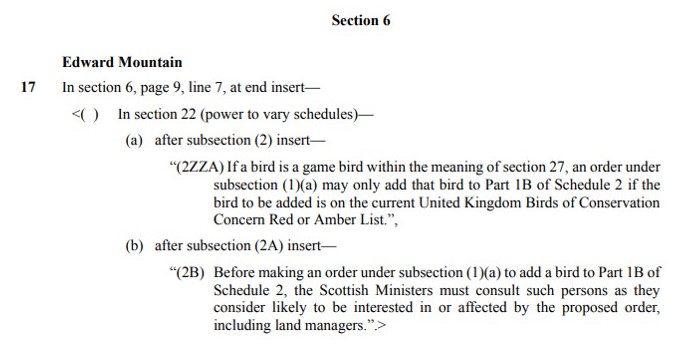

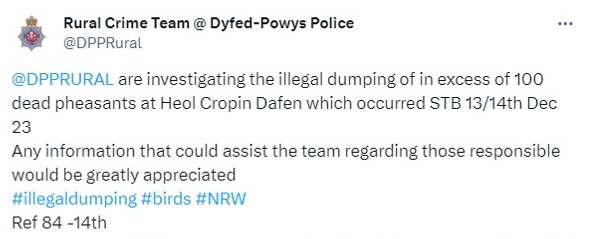

We have a set of strict criteria that game shooting leases must adhere to. This includes the location of release pens, which must not impact priority habitats including ancient woods, the use of lead ammunition and medicated grit, which we will no longer permit, and requirements to ensure shoots do not hinder people’s access to our places. Moreover, we do not permit any shooting of red-listed birds of conservation concern and will only permit limited wildfowling of green and amber-listed birds on a species-by-species basis where statutory agency evidence confirms this is not damaging to local populations. We remain totally opposed to the illegal persecution of birds of prey and all other wildlife crimes and take action to combat these criminal practices, working closely with our partners in the Police, statutory agencies, and the RSPB, to report and convict those who commit these offences.

We will implement these changes when shoot leases come up for renewal, or sooner if break-clauses in agreements allow. Our approach will be kept under constant review, as will any position we might take on licencing of grouse shooting in the uplands‘.

I think this is a sensible and measured step forward by the National Trust. This new policy will effectively put an end to intensively-managed driven grouse shooting on National Trust moors, without actually banning it, and turns the focus back to nature-based, regenerative and sustainable management instead. No more burning on peat soils, no medicated grit, no lead ammunition, limited predator control and no more measuring ‘success’ by the number of birds shot in a day/season.

It doesn’t remove the threat to wildlife (especially raptors) from neighbouring, privately-owned grouse moors but it sets a new standard for grouse moor management and its effects will be interesting to monitor.

Personally I think this model is the only hope the grouse shooting industry has of staying alive and if these or similar practices aren’t quickly adopted more widely then the industry is doomed. I think the driven grouse shooting industry recognises this too, hence its hysteria over proposed regulations to reform grouse shooting in Scotland. The days of intensive and unsustainable driven grouse shooting are numbered, and they know it.

I’m also pleased to see that the National Trust’s new policy extends to all gamebird shooting, including pheasants, red-legged partridges and woodcock and isn’t just limited to driven grouse shooting. Bravo.

This policy shift will undoubtedly put the National Trust in the firing line of the game shooting industry – indeed, I’ve already read one ‘article’ attempting to undermine Craig Best’s professional reputation and expertise in a nasty, vindictive attack. It’s what they do.

I applaud Craig’s efforts on this issue, and those of the wider National Trust management team. Ten years ago to expect this level of progress would have been unthinkable.