A couple of months ago an article was published in the Mail on Sunday about the ‘mysterious’ death of a satellite-tagged goshawk on the Queen’s Sandringham Estate in Norfolk (see here).

We blogged about it (here) and mentioned a number of other raptor-related police investigations that had been undertaken on or near the estate. On the back of that blog, somebody contacted us and asked why we hadn’t included on our list ‘the confirmed illegal poisoning of a sparrowhawk a few years ago’? We hadn’t included it because we didn’t know anything about it, so we thought we’d do some digging.

First of all we did a general internet search. If there had been a confirmed raptor poisoning on the Queen’s Sandringham Estate then surely that would have made a few headlines, right? We didn’t find any record of it.

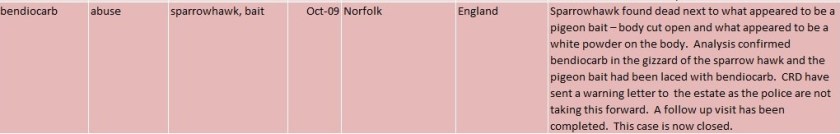

So then we started looking at the government’s database on pesticide misuse and abuse (the Wildlife Incident Investigation Scheme, often shortened to ‘the WIIS database’). In that database we found the following entry:

Although this entry showed that a poisoned sparrowhawk and a poisoned bait had been discovered in Norfolk in October 2009, as usual, no specific location was given. We were, however, intrigued by the ‘Notes’ column, that said even though a confirmed poisoning had occurred, the police were ‘not taking this forward’ and instead the CRD (Chemical Regulation Directorate, which is part of the Health & Safety Executive) had ‘sent a warning letter to the estate’.

So we thought we’d submit an FoI to the CRD to ask for a copy of that warning letter, because it might reveal the name of the estate where the poisoned sparrowhawk and poisoned bait had been found. We were also curious about the content of that warning letter – if there had been a confirmed poisoning, why was a warning letter considered to be a preferred option to a prosecution?

We’ve now received the FoI response and have been working our way through the various files.

The first file we looked at was a series of correspondence letters between the CRD and the estate. The estate’s name had been redacted throughout. Hmm. The letters are really worth reading though – there are some pretty hostile attitudes on display and there’s clearly no love lost between CRD and the estate manager! Download here: CRD correspondence with Estate_2010

There’s also a letter from a Natural England officer to the estate, asking for various documents relating to pesticide risk assessments, gamekeeper contracts, and gamekeeper training certificates: Natural England letter to Estate 19Oct2009

We gathered from the CRD/estate correspondence that no further evidence of Bendiocarb had been found during a Police/Natural England search of the estate which is presumably why Norfolk Police didn’t charge anybody for the poisoned sparrowhawk and poisoned bait, because there was no way of linking it to a named individual. Anybody could have placed the poisoned bait. But a series of alleged offences relating to pesticide storage had apparently been uncovered and it was these issues to which the CRD warning letter referred, although it’s clear from the estate’s letters to CRD that the estate disputed the alleged offences.

While that’s all very interesting, we were still in the dark about the name of the estate where all this had happened. That is, until we read another file that had been released as part of the FoI: CRD_lawyer discussion of FEPA exemption

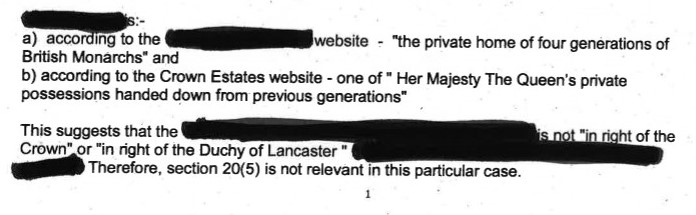

This file contains correspondence between the CRD and a number of lawyers. They were discussing whether the estate had exemption under Section 20(5) of the Food and Environment Protection Act 1985 (FEPA). This exemption applies to land that is owned ‘in Crown interest’. There was a great deal of discussion about whether this estate (name redacted) was owned by the Crown or was privately owned by the Queen.

The lawyers decided that this estate (name redacted) was in fact privately owned by the Queen, and therefore exemption under Section 20(5) of FEPA did not apply. The lawyers had reached this conclusion after several internet searches on the status of this estate (name redacted) had been completed. What the FoI officer failed to do was redact the search phrases that had been used to reach their decision. Those search phrases included:

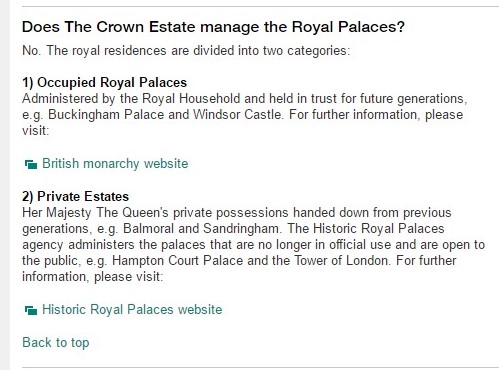

Now, if you Google the exact search phrase listed under (a) above (“the private home of four generations of British Monarchs“) you are directed to this website:

And if you go to the Crown Estates website and search for the exact search phrase listed in (b) above (“according to the Crown Estates website – one of Her Majesty the Queen’s private possessions handed down from previous generations“), you find this:

It’s all very interesting, isn’t it? This isn’t conclusive evidence that it was Sandringham Estate, of course, and there is no suggestion whatsoever that anyone associated with the Sandringham Estate was involved with placing a poisoned bait, although it is clear a poisoned sparrowhawk and a poisoned bait were found on a Royal estate in Norfolk (how many Royal estates are there in Norfolk?).

But what this does highlight, again, is the complete lack of transparency when the authorities investigate the discovery of highly toxic poisonous baits laid out on private estates with game-shooting interests, or the discovery of illegally killed raptors on privately owned estates with game-shooting interests.

Why has this case been kept secret since 2009?

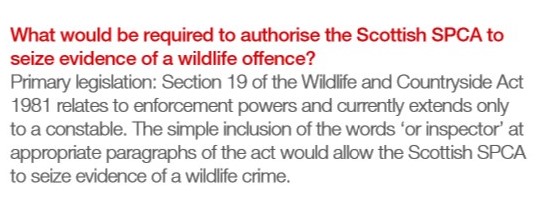

As we await the long-overdue decision on whether the Scottish Government will approve an increase in investigatory powers for the SSPCA (see

As we await the long-overdue decision on whether the Scottish Government will approve an increase in investigatory powers for the SSPCA (see

The

The

Two weeks ago, we blogged about how the Crown Office & Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS – the public prosecutors in Scotland) had dropped a long-running vicarious liability prosecution against landowner Andrew Duncan, who was alleged to have been vicariously liable for the crimes of his gamekeeper, who had killed a buzzard on the Newlands Estate in 2014. When pressed for a reason behind the decision to drop the vicarious liability case, the Crown Office said it was “not in the public interest to continue” but did not provide any further detail of how, or why, that decision had been reached (see

Two weeks ago, we blogged about how the Crown Office & Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS – the public prosecutors in Scotland) had dropped a long-running vicarious liability prosecution against landowner Andrew Duncan, who was alleged to have been vicariously liable for the crimes of his gamekeeper, who had killed a buzzard on the Newlands Estate in 2014. When pressed for a reason behind the decision to drop the vicarious liability case, the Crown Office said it was “not in the public interest to continue” but did not provide any further detail of how, or why, that decision had been reached (see  Serial raptor persecution denier Doug McAdam is to stand down as CEO of Scottish Land & Estates, according to a statement on SLE website (

Serial raptor persecution denier Doug McAdam is to stand down as CEO of Scottish Land & Estates, according to a statement on SLE website (

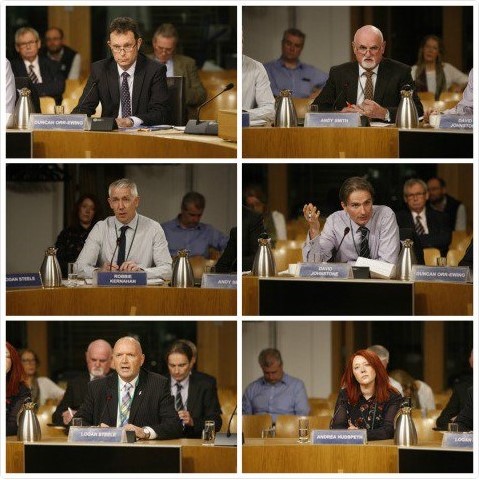

Andy Wightman has launched a crowdfunding appeal to help support his fight against a defamation case being brought against him by Wildcat Haven Enterprises CIC. The pursuer is also seeking an astonishing £750,000 in damages and if successful, would render Andy bankrupt which would result in him being ineligible to continue to serve as an MSP.

Andy Wightman has launched a crowdfunding appeal to help support his fight against a defamation case being brought against him by Wildcat Haven Enterprises CIC. The pursuer is also seeking an astonishing £750,000 in damages and if successful, would render Andy bankrupt which would result in him being ineligible to continue to serve as an MSP.