Last October, the Countryside Alliance launched a scathing attack on the RSPB’s latest annual Birdcrime Report (Birdcrime 2013). The link to their article has mysteriously ‘disappeared’ from their website, so here’s a copy we took:

Last October, the Countryside Alliance launched a scathing attack on the RSPB’s latest annual Birdcrime Report (Birdcrime 2013). The link to their article has mysteriously ‘disappeared’ from their website, so here’s a copy we took:

Thursday, 30 October 2014, Countryside Alliance website:

Countryside Alliance Director for Shooting Adrian Blackmore writes: The RSPB’s Birdcrime Report for 2013, which was published on Thursday 30th October 2014, provides a summary of the offences against wildlife legislation that were reported to the RSPB in 2013. It should be noted that in 2009, the RSPB took the decision to focus on bird crime that affected species of high conservation concern, and crime that it regarded as serious and organized. The figures supplied do not therefore give a total figure for wild bird crime in the UK in 2013, and they are not comparable with figures provided for years prior to 2009.

As is becoming increasingly the case, the report makes sweeping allegations against the shooting community, and grouse shooting in particular – allegations that are not consistent with the evidence provided. It claims that activity on grouse moors is having a serious impact on some of our most charismatic upland birds, and that current measures have failed to find a solution. The report claims that “over the years, a steady stream of grouse moor gamekeepers have been prosecuted for raptor persecution crimes”, and lists each of the offences for which those gamekeepers have been found guilty between 2001 and 2013. Over that 13 year period, 20 gamekeepers employed on grouse moors (an average of 1.5 per year) are shown as having been prosecuted, but according to the RSPB’s birdcrime reports for each of those years, the total number of individual prosecutions involving wild birds totalled 526 individuals. Given that grouse moor keepers therefore represent a mere 4% of those prosecuted in the courts, one can only wonder why the RSPB should choose not to focus on the occupations of the other 96%.

The RSPB also states in the report that “it believes it is the shooting industry as a whole, not individual gamekeepers, that is primarily responsible for raptor persecution in the UK”. It has therefore repeated its call for: political parties to introduce licensing of driven grouse shooting after the election; the introduction of an offence of vicarious liability in England; increasing the penalties available to courts for wildlife offences; and for game shooting to be regulated with an option to withdraw the ‘right’ of an individual to shoot game or businesses to supply shooting services for a fixed period following conviction for a wildlife or environmental offence.

For the third year running, the RSPB has included a piece of research in its Birdcrime Report that is intentionally misleading. Both the 2011 and 2012 reports covered in detail a research paper which claimed that peregrines on or close to intensive grouse moor areas bred much less successfully than those in other habitats, and that persecution was the reason for this. That same research paper is covered again in the 2013 Birdcrime report. The research in question used data from 1990 – 2006 and at the time it was published a representation was made to the National Wildlife Crime Unit which resulted in a caveat being circulated to all Police Wildlife Crime Officers in the UK explaining that the data used in the paper was out of date, and that in using such information there was danger that the research paper suggested a current situation. For the RSPB is well aware of that caveat, and to include this once again makes a complete mockery of its previously stated belief that reliable data are essential to monitoring the extent of wildlife crime.

Summary of statistics

341 reported incidents of illegal persecution in 2013 – a reduction of 24% since 2012 when there were 446 reported incidents, and well below the previous 4 year average of 573.

164 reported incidents of the shooting and destruction of Birds of Prey which included the confirmed shooting of 49 individual birds of which only 7 took place in counties associated with grouse shooting in the North of England.

74 reports of poisoning incidents involving the confirmed poisoning of 58 Birds of Prey of which only 2 occurred in counties in the North of England where grouse shooting occurs.

In total, there were 125 confirmed incidents of illegal persecution against Birds of Prey in 2013. Just 18 of those occurred in counties in the North of England where grouse shooting takes place, and none of those have been linked to grouse shooting.

Of the 32 individual prosecutions involving wild birds in 2013, only 6 individuals were game keepers, and one of those was found not guilty. Therefore, of those prosecuted, only 16% were gamekeepers and only 6% of the 32 cases involved birds (buzzards) that had been killed. Only one of the cases concerned an upland keeper employed by an estate with grouse shooting interests, and that case did not involve the destruction of a bird of prey.

Of the 14 incidents of nest robberies reported in 2013, only 3 were confirmed, one of which involved the robbery of at least 50 little tern nests.

There is no evidence to support the RSPB’s allegation of persecution of birds of prey by those involved in grouse shooting. The RSPB’s Birdcrime Reports show that between 2001 and 2013 there were 526 individual prosecutions involving wild birds, and according to its 2013 report only 20 of those individuals (4%) were actually gamekeepers employed on grouse moors.

Land managed for grouse shooting accounts for just 1/5th of the uplands of England and Wales.

The populations of almost all our birds of prey are at their highest levels since record began, and only the hen harrier and the white-tailed eagle are red listed as species of conservation concern.

REPORTED INCIDENTS IN 2013

In 2013, the RSPB received 341 reported incidents of wild bird crime in the UK, the lowest figure since 2009. This represents a reduction of 24% since 2012 when there were 446 reported incidents, and well below the previous 4 year average of 573.

SHOOTING INCIDENTS

As in previous years, the, the most commonly reported offence in 2013 was the shooting and destruction of birds of prey, with 164 reported incidents in 2013. Of these, the shooting of 49 birds of prey are shown in the report as being confirmed, of which 7 were in counties of the North of England where grouse shooting takes place. The remaining 23 incidents that were confirmed in England occurred elsewhere.

POISON ABUSE INCIDENTS

During 2013 there were 74 reports of poisoning incidents involving the confirmed poisoning of 58 Birds of Prey of which only 2 occurred in counties in the North of England where grouse shooting takes place:

ILLEGAL TRAPPING AND NEST DESTRUCTION

There were 18 confirmed incidents of illegal trapping of birds of prey in 2013, and no confirmed cases of nest destructions, compared to 2012 when there had been 10 incidents of nests being destroyed. Although this figure of 18 is an improvement on that for 2012, it is still above the previous 4 year average of 14 incidents.

WILD BIRD RELATED PROSECUTIONS

In 2013 there were 32 individual prosecutions involving wild birds. Only 6 of those individuals were game keepers, and one of those was found not guilty. Therefore, of those prosecuted, only 16% were gamekeepers and only 6% of the 32 cases involved birds (buzzards) that had been killed. Only one of the cases concerned an upland keeper employed by an estate with grouse shooting interests, and that case did not involve the destruction of a bird of prey:

CONCLUSION

It is clear from its 2013 Birdcrime Report that the RSPB is continuing in its efforts to promote an anti-shooting agenda, especially against driven grouse shooting. It has less to do with aconcern about birds and more about ideology and a political agenda. Like reports of recent years, the 2013 Birdcrime Report is deliberately misleading, and many readers will invariably take at face value the claims and accusations that have been made. Many of these are serious, and made without the necessary evidence with which to substantiate them.

ENDS

The reason, perhaps, this article has mysteriously ‘disappeared’ from the CA’s website can probably be explained by the following…..

The reason, perhaps, this article has mysteriously ‘disappeared’ from the CA’s website can probably be explained by the following…..

The Countryside Alliance used this article to lodge a complaint against the RSPB with the Charity Commission. The CA’s claim was based on this:

“The report [Birdcrime 2013] makes sweeping allegations against the shooting community, and grouse shooting in particular – allegations that are not consistent with the evidence provided [in Birdcrime 2013]”.

The Charity Commission was obliged to investigate the CA’s complaint that the RSPB had ‘mis-used’ data and had made ‘un-founded allegations’ and they have now issued their verdict – they have rejected every single complaint made by the Countryside Alliance against the RSPB.

Strangely, although the Charity Commission’s response letter was sent to the CA on 7th January 2015, the findings have not appeared on the CA’s website. Can’t think why. Anyway, here’s a copy for those who want to read it – it’s really rather good:

Charity Commission response to Countryside Alliance complaint re RSPB Jan 2015

Not to be deterred by making yet another ‘embarrassing blunder‘, this week the Countryside Alliance wrote a response to the sentencing of goshawk-bludgeoning gamekeeper George Mutch, sent to jail for four months for his raptor-killing crimes. The CA’s response starts off well, condemning Mutch’s actions, but then it all goes badly wrong. According to the CA, it’s the RSPB’s ‘wider policy’ that is driving the continued illegal persecution of raptors!

You couldn’t make this stuff up. Why is it so hard for the game-shooting industry to take responsibility for their actions instead of continually trying (and failing) to discredit the RSPB? Is it because they have no intention whatsoever of addressing the widespread criminality within their ranks and so they churn out all this anti-RSPB rhetoric as a distraction technique? Nothing to do with the RSPB being so effective at exposing and documenting the game-shooting industry’s crimes, of course.

Expect more ludicrous attacks on the RSPB over the coming weeks and months….a predictable response from an industry unable, or unwilling, to self-regulate and undoubtedly feeling the pressure of scrutiny and demand for change from an increasingly well-informed public.

The link to the CA’s latest absurd accusation can be found here, but just in case it also mysteriously ‘disappears’, here’s the full text. Enjoy!

Countryside Alliance website

16th January 2015

‘Shooting, livelihoods and raptors’

The illegal killing of birds of prey is about the most selfish crime it is possible to commit because even if there are short term benefits for the preservation of game (and those benefits are as likely to be perceived as real) they will always be outweighed by the long term damage to the shooting industry as a whole.

That is why the Alliance has no hesitation in condemning an Aberdeenshire gamekeeper who was sentenced to four months in prison earlier this week for four offences including the killing of a goshawk.

Raptors as a whole may be the biggest success story in British birds with numbers having increased hugely as a result of legal protection and reintroduction, but some species remain rare and killing them for the sake of providing more birds to shoot is never going to be anything but a political and PR disaster.

The RSPB collected the evidence which convicted that gamekeeper and was understandably pleased with the outcome of the case. Whilst its actions in relation to individual cases like this are entirely justified the Society must, however, consider whether its wider policy is actually helping to perpetuate, rather than reduce, illegal persecution.

This might sound a strange statement, but it is worth considering the RSPB’s own history and how other wildlife conflicts have been resolved. The RSPB was founded by a group of women appalled by the trade in exotic feathers for ladies’ hats. Its first campaign was not aimed at prosecuting the people killing birds, but at removing the causes of persecution, which in that case was the high value of feathers. By reducing demand for rare birds it removed the economic imperative for persecution.

One argument might be to simply ban shooting and with it one of the main reasons someone might have for killing a raptor. However, that policy would create far greater conflict and remove the many positive environmental, economic and social benefits of shooting which far outweigh the negatives of any associated raptor killing.

Another, we would argue far more logical, approach would be to consider the causes of any illegal raptor killing and how the drivers for that activity could be removed. In two areas in particular the RSPB seems unwilling to consider proposals which tackle the causes of persecution, as well as persecution itself.

Firstly by refusing to endorse proposals for hen harrier ‘brood management’ which would give assurances to upland keepers that colonies of hen harriers could not make their moors unviable and their jobs redundant. And secondly by opposing absolutely any management, even non-lethal, of the burgeoning buzzard population even if they are having a significant economic impact on game shooting.

We are not suggesting that these management practices must take place, but surely an agreement that they could be used where absolutely necessary to protect livelihoods would make it less likely that people would make the wrong decision about illegal killing?

END

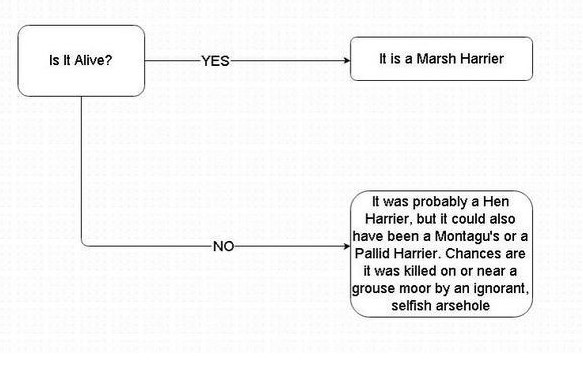

With depressing familiarity, news has emerged of the illegal killing of yet another hen harrier.

With depressing familiarity, news has emerged of the illegal killing of yet another hen harrier.

Over the last year or so (and especially over the last few months) there has been an increasing amount of media coverage regarding the political and ecological status of hen harriers in the Republic of Ireland. Much of the media coverage has come from one particular Irish newspaper, heavily influenced by political spin doctors (the equivalent of the Telegraph/Daily Mail in the UK). When these newspaper articles are shared with a UK audience on social media, without an accompanying critique or even a vague understanding of the politics behind each story, a one-sided view of the situation can be accepted as being ‘factual’.

Over the last year or so (and especially over the last few months) there has been an increasing amount of media coverage regarding the political and ecological status of hen harriers in the Republic of Ireland. Much of the media coverage has come from one particular Irish newspaper, heavily influenced by political spin doctors (the equivalent of the Telegraph/Daily Mail in the UK). When these newspaper articles are shared with a UK audience on social media, without an accompanying critique or even a vague understanding of the politics behind each story, a one-sided view of the situation can be accepted as being ‘factual’. But if that isn’t enough the private forest lobby has been busy winning over the farming organisations with offers of lucrative tax-free grants for private forestry, leading to calls by the Irish Farmers Association for an end to a moratorium on new forestry in the SPAs (see here

But if that isn’t enough the private forest lobby has been busy winning over the farming organisations with offers of lucrative tax-free grants for private forestry, leading to calls by the Irish Farmers Association for an end to a moratorium on new forestry in the SPAs (see here  Windfarms, harrier persecution and those ghost SPAs

Windfarms, harrier persecution and those ghost SPAs Up until yesterday, we had a lot of respect and admiration for the Hawk & Owl Trust. They’ve got some fantastic staff and volunteers, their conservation work has been exemplary, as has their educational work, and they’ve stood shoulder to shoulder with the rest of us to make a stand against the illegal persecution of raptors. Such was their unity, in 2013 they even walked away from the ridiculous Hen Harrier Dialogue shortly after the RSPB and the Northern England Raptor Forum had walked. They were one of us, with shared ideals and whose patience with the grouse moor owners had been sucked dry. Read their exit statement

Up until yesterday, we had a lot of respect and admiration for the Hawk & Owl Trust. They’ve got some fantastic staff and volunteers, their conservation work has been exemplary, as has their educational work, and they’ve stood shoulder to shoulder with the rest of us to make a stand against the illegal persecution of raptors. Such was their unity, in 2013 they even walked away from the ridiculous Hen Harrier Dialogue shortly after the RSPB and the Northern England Raptor Forum had walked. They were one of us, with shared ideals and whose patience with the grouse moor owners had been sucked dry. Read their exit statement  Last October, the Countryside Alliance launched a scathing attack on the RSPB’s latest annual Birdcrime Report (

Last October, the Countryside Alliance launched a scathing attack on the RSPB’s latest annual Birdcrime Report ( The reason, perhaps, this article has mysteriously ‘disappeared’ from the CA’s website can probably be explained by the following…..

The reason, perhaps, this article has mysteriously ‘disappeared’ from the CA’s website can probably be explained by the following…..

Sometimes, we despair.

Sometimes, we despair. There’s been a lot of interesting articles in the news media over the last few days. Unfortunately we’ve been too busy to blog about these in details so here’s a quick round up:

There’s been a lot of interesting articles in the news media over the last few days. Unfortunately we’ve been too busy to blog about these in details so here’s a quick round up: