Regular blog readers will know that we’ve frequently had cause to criticise Police Scotland’s response to suspected wildlife crimes that have been reported to them. Well, we’re about to do it again over their mishandling of two recently reported suspected wildlife crime incidents, one in Dumfries & Galloway and one in South Lanarkshire.

Regular blog readers will know that we’ve frequently had cause to criticise Police Scotland’s response to suspected wildlife crimes that have been reported to them. Well, we’re about to do it again over their mishandling of two recently reported suspected wildlife crime incidents, one in Dumfries & Galloway and one in South Lanarkshire.

Before we get to the details of the latest fiascos, have a read of the following text that appeared in on page 32 of RSPB Scotland’s recently published 20-year review of raptor persecution:

‘After the initial finding or reporting of a potential wildlife crime incident, a rapid and properly-directed follow-up is essential to prevent any evidence being removed by the perpetrator, further wildlife falling victim to illegal poisons or traps, removal of victims by scavengers or decomposition of victims. Any of these factors can render obtaining forensic evidence or an accurate post-mortem impossible. In our experience, however, the speed and effectiveness of follow-up investigations and securing of evidence has been highly variable‘.

It is apparent, from the following two incidents, that Police Scotland is still failing to get the basics right.

Incident 1

A member of the public found a decomposing dead buzzard on a grouse moor in an area well-known for its history of raptor persecution. The corpse was found on Saturday 19th December 2015. It was reported to members of the local Raptor Study Group who went to the grid reference provided (just 150 yards from a main road) and confirmed it was indeed a dead buzzard. They reported it to Police Scotland on the morning of Monday 21st December and were told that an officer would attend to collect the corpse and send it for post mortem. Raptor workers went back to the site the next day (Tuesday 22nd) and the corpse was still there. They returned on Wednesday 23rd and the corpse was still there. They returned on Thursday 24th and the corpse was still there. They returned on Saturday 26th and the corpse was still there. They returned on Sunday 27th and the corpse was still there. They returned on Monday 28th December, one week after reporting it to the police, and the corpse had gone. Whether it had finally been collected by Police Scotland or whether it had been scavenged by an animal or removed by a gamekeeper, nobody knows.

Incident 2

On 28th December 2015 a member of the public found a freshly-dead buzzard in a wood, with no obvious cause of death. Previously, snares placed over the entrance of a badger sett had been found in this wood. The nearest grouse moor is approx 1.5 miles away. Because of the history of the location, the member of the public was suspicious and took the buzzard home and called Police Scotland on 101. The member of the public was told by the Police Scotland call operator that the police were unable to help. “In fact at one point he suggested that I take it to a vet or call the ‘RS bird people’. He said that the police could only help if they actually caught the offenders at the scene in which case they would be prosecuted for poaching“. Undeterred, the member of the public found an email address for the local police wildlife crime officer but got an out-of-office reply saying nobody was available until 17th January 2016. Fortunately, a local raptor worker was able to collect the corpse and got in touch with RSPB Scotland who organised for the bird to be sent for post mortem.

The Police Scotland response to both of these incidents was appalling. Now, it may well turn out that in both cases the birds died of natural causes and no crimes had been committed. However, it’s equally plausible, especially given the incident locations, that these birds had been killed illegally. The point is, it’s Police Scotland’s job to investigate these incidents and determine whether a crime has been committed. Their action (and inaction) in these two cases could have severely compromised the outcome.

You may remember a similar incident, not a million miles from these two locations, that happened in 2014. In that case, a dead peregrine had been found by a member of the public but Police Scotland again failed to attend the scene, saying it wasn’t a police matter (see here). The peregrine was collected by RSPB Scotland and the post mortem revealed it had been poisoned with the banned pesticide Carbofuran. Police Scotland’s failure to attend that incident caused quite a stir, with the story being covered in a national newspaper (here) and it also led to questions being asked in Parliament about Police Scotland’s failed response (see here). Police Scotland denied they’d done anything wrong!

In March last year, following the publication of a damning report on the police’s response to various types of wildlife crime incidents over several years, Police Scotland launched an all-singing-all-dancing Wildlife Crime Awareness Campaign, endorsed by the Environment Minister (see here). This campaign (which we welcomed – see here) focused on the six national wildlife crime priorities, including raptor persecution, and included the production of all sorts of campaign material (posters etc) designed to encourage members of the public to report suspected wildlife crimes. That’s all good, but what’s the point if Police Scotland then can’t get their act together to provide a professional response when members of the public report suspicious incidents?

Is it really so hard?

If they’re under-resourced, fine, then they should say so and should be supporting the move to increase the investigatory powers of the SSPCA, not trying to block it. Talking of which, when will Environment Minister Dr Aileen McLeod make a decision on the SSPCA’s powers? It’s now been 16 months since the public consultation closed. Getting to grips with wildlife crime is supposed to be a ‘key priority’ for the Scottish Government. In February, it’ll be five years since the consultation was first proposed!

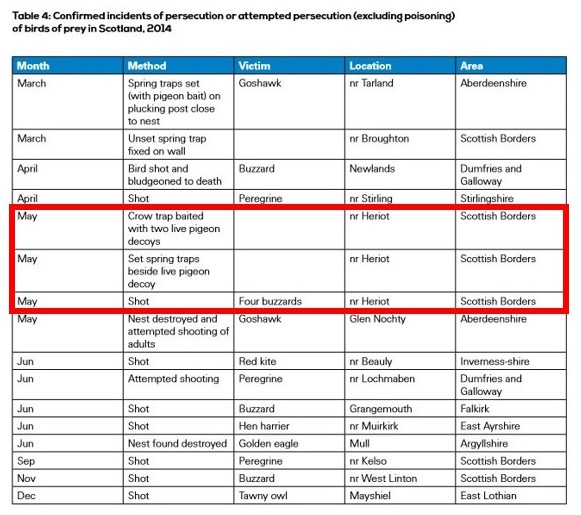

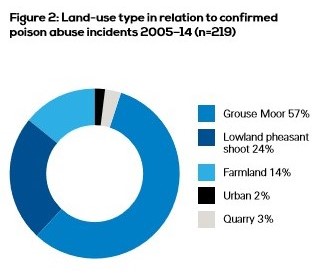

Yesterday the RSPB published its latest figures on illegal raptor persecution in Scotland.

Yesterday the RSPB published its latest figures on illegal raptor persecution in Scotland.

This is good news, after the disappointment of the recent failure to prosecute another vicarious liability case on the Kildrummy Estate (see

This is good news, after the disappointment of the recent failure to prosecute another vicarious liability case on the Kildrummy Estate (see

Last month we blogged about the failure of the Crown Office to initiate a vicarious liability prosecution in the Kildrummy case (see

Last month we blogged about the failure of the Crown Office to initiate a vicarious liability prosecution in the Kildrummy case (see  Regular blog readers will know that in October 2014, gamekeeper Allen Lambert was convicted of a series of wildlife crime offences on the Stody Estate, Norfolk, including the mass poisoning of birds of prey (10 buzzards and one sparrowhawk) which had been found dead on the estate in April 2013. He was also convicted of storing banned pesticides and other items capable of preparing poisoned baits (a ‘poisoner’s kit’) and a firearms offence (see

Regular blog readers will know that in October 2014, gamekeeper Allen Lambert was convicted of a series of wildlife crime offences on the Stody Estate, Norfolk, including the mass poisoning of birds of prey (10 buzzards and one sparrowhawk) which had been found dead on the estate in April 2013. He was also convicted of storing banned pesticides and other items capable of preparing poisoned baits (a ‘poisoner’s kit’) and a firearms offence (see

The High Court has this morning ruled that Natural England acted unlawfully

The High Court has this morning ruled that Natural England acted unlawfully  As absurd as it is, the bottom line is that DEFRA (and thus Natural England, acting on DEFRA’s behalf), permits gamekeepers (even those with criminal convictions) to apply for licences to kill protected native species like the buzzard, to allow the wholesale slaughter of millions of non-native gamebirds like pheasants, just for fun. There’s something fundamentally askew with that logic, even if you’re a die-hard supporter of game-bird shooting. A recent analysis of the GWCT’s National Gamebag Census revealed that by 2011, approx 42 million pheasants and almost 9 million red-legged partridges were released annually into the British countryside, for ‘sport’ shooting. The impact on biodiversity of releasing 50 million non-native gamebirds hasn’t been formally assessed. The game-shooting industry should accept that if they’re releasing birds in such magnitude, they should expect losses. How many are killed on the roads? An educated guess would suggest it’s a far higher number than the known 1-2% lost to raptors. If the game-shooting industry can’t operate without accepting such losses (as they claim they can’t), then it’s pretty clear evidence that this industry is unsustainable and as such, has no future.

As absurd as it is, the bottom line is that DEFRA (and thus Natural England, acting on DEFRA’s behalf), permits gamekeepers (even those with criminal convictions) to apply for licences to kill protected native species like the buzzard, to allow the wholesale slaughter of millions of non-native gamebirds like pheasants, just for fun. There’s something fundamentally askew with that logic, even if you’re a die-hard supporter of game-bird shooting. A recent analysis of the GWCT’s National Gamebag Census revealed that by 2011, approx 42 million pheasants and almost 9 million red-legged partridges were released annually into the British countryside, for ‘sport’ shooting. The impact on biodiversity of releasing 50 million non-native gamebirds hasn’t been formally assessed. The game-shooting industry should accept that if they’re releasing birds in such magnitude, they should expect losses. How many are killed on the roads? An educated guess would suggest it’s a far higher number than the known 1-2% lost to raptors. If the game-shooting industry can’t operate without accepting such losses (as they claim they can’t), then it’s pretty clear evidence that this industry is unsustainable and as such, has no future.