RSPB press release, 22 May 2018:

THREE HEN HARRIERS DISAPPEAR IN SUSPICIOUS CIRCUMSTANCES

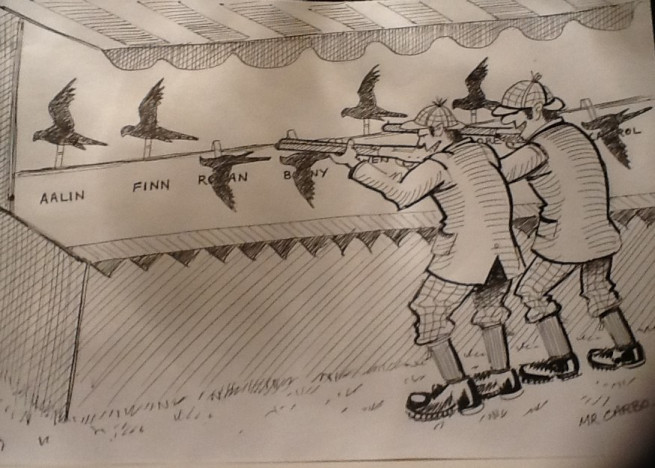

Police and the RSPB are appealing for information following the disappearance of three protected, satellite-tagged hen harriers in Scotland and Cumbria.

After monitoring her progress since she fledged last June, a hen harrier named Saorsa suddenly ceased sending transmissions in February 2018 whilst located in the Angus Glens, Scotland. She has not been seen or heard of since.

A male bird, named Blue, then raised concerns in March this year when his tag, which had also been functioning perfectly, suddenly and inexplicably cut out near Longsleddale, Cumbria.

In the same month, a tagged bird named Finn – after young conservationist Findlay Wilde – vanished near Moffat, Scotland. Finn was tagged as a chick in 2016 from a nest in Northumberland, one of only three hen harrier nests to fledge young in the whole of England that year.

[RPUK map]:

RSPB Investigations staff conducted a search for all three birds, but no tags or bodies were found. Where tagged hen harriers have died of natural causes in the past, the tags and bodies have generally been recovered. Cumbria Police and Police Scotland are making local enquiries.

Hen harriers are one of the UK’s rarest birds of prey with just three successful nests recorded in England in 2017. There is a slightly larger population in Scotland. These slight, agile birds of prey nest on the ground, often on moorland. Like all wild birds, they are protected by law under the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981. But, despite full legal protection, studies show that their declining population is largely associated with human persecution.

Several birds have been fitted with a lightweight satellite tag as part of the EU-funded Hen Harrier LIFE project to help build a better understanding of hen harriers, their movements and the threats they face. Since the project began in 2014, a number of tagged hen harriers have disappeared in similarly inexplicable circumstances.

Cathleen Thomas, Hen Harrier LIFE Project Manager, said “The UK population of hen harriers is really hanging in the balance and the disappearance of these three birds is extremely troubling. These tags are over 90% reliable and capable of transmitting long after a bird has died. If these birds had died of natural causes we would expect to recover both the tag and the body. But this has not been the case.”

Findlay Wilde said “In the short time we followed Finn, we went through every emotion possible; from the excitement of knowing she had safely fledged to the nagging worries that she was settling in high-risk areas; and then of course to the worst news of all. Finn isn’t just another statistic in growing listing of missing hen harriers. Her life mattered, and she mattered to me.”

If you have any information relating to any of these incidents, call police on 101. Or to speak to RSPB investigations in confidence, call the Raptor Crime Hotline on 0300 999 0101.

ENDS

Dr Cathleen Thomas of the RSPB’s Hen Harrier LIFE Project has written a blog which provides more details of each of the missing harriers – here.

Finn Wilde has also written a blog about the loss of ‘his’ hen harrier – here

The news of these three suspicious disappearances will come as absolutely no surprise to anybody. And neither will the responses of the game-shooting industry, as it trots out the usual, well-rehearsed denials and fake concerns. We’ve seen it time and time again, whether it be about vanishing hen harriers or vanishing golden eagles, and we’ll doubtless see it many more times again. That it’s allowed to continue without sanction is a bloody scandal.

The two young hen harriers that disappeared in Scotland are very interesting.

Saorsa hatched on the Balnagown Estate in Sutherland in 2017. She disappeared in the Angus Glens – a well-known blackspot for illegal raptor persecution and, ironically, in the consituency of Mairi Gougeon MSP, the Hen Harrier Species Champion.

[Photo of Saorsa in the nest, by Brian Etheridge]

We believe the Balnagown Estate was one of several participating in the controversial Heads Up for Hen Harriers Project, whereby estates agree to have cameras installed at hen harrier nest sites to identify the cause of nest failure and help understand the species’ on-going population decline. We’ve blogged about this greenwashing scam many times, and we’ll be doing so again in the very near future, but for now, the fate of Hen Harrier Saorsa is a good demonstration of how futile the project is. She was raised on an estate where there are absolutely no concerns about illegal raptor persecution whatsoever (there’s no driven grouse shooting on the Balnagown Estate) but once she dispersed from the relative safety of that estate, she was at risk. Heading for the Angus Glens, where successfully breeding hen harriers have been absent since 2006, was a seemingly fatal mistake.

Hen Harrier Finn, named after young conservationist Findlay Wilde, hatched on protected Forestry Commission land in Northumberland, 2016. Finn’s last tag transmission came from near Moffat, SW Scotland, which is the location of the controversial golden eagle translocation project, due to start this year.

[Photo of Finn by Martin Davison]

Now, let’s assume that DEFRA’s outrageous hen harrier brood meddling plan had been in place in 2016, and that the Forestry Commission had agreed to participate, then Finn and her three siblings would have been removed from the nest, reared in captivity and then released back to the wild in mid-August, close to their natal territory. This brood meddling plan is purported to ‘protect’ young hen harriers, and DEFRA / Natural England / the grouse-shooting industry all claim that this technique will help increase the population of hen harriers. It’s another greenwashing scam.

Would brood meddling have saved Finn? No, of course not, because Finn ‘disappeared’ in suspicious circumstances (presumed to have been illegally killed) in March, several months after she would have been returned to the wild post-brood meddling. So as many of us have been arguing for years, brood meddling will not help hen harriers because it doesn’t address the fundamental issue of illegal raptor persecution, year-round, that has brought this species to its knees.

Brood meddling is due to begin in England this year, but there are two on-going legal challenges, via judicial review, from Mark Avery and the RSPB. We await further news on these cases.

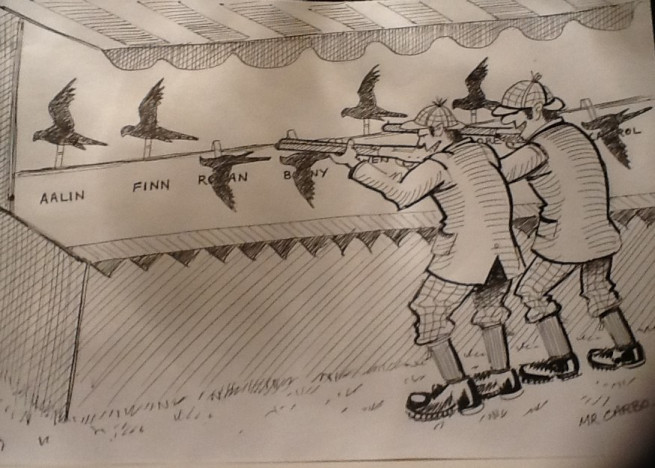

Meanwhile, across the grouse moors of northern England and Scotland, it’s business as usual for the hen harrier killers.

[Cartoon by Mr Carbo]

UPDATE 24 May 2018: Laughable statement from SGA on missing satellite-tagged hen harriers (here)

UPDATE 25 January 2019: SGA fabricates ‘news’ on missing sat-tagged hen harrier Saorsa (here)