We have been passed a document that shows the new protocol for the collection of evidence in raptor persecution crimes. The protocol has apparently been agreed by the Scottish Raptor Persecution Priority Delivery Group (SRPPDG). This group includes representatives from the Scottish Government, Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH), Scottish Gamekeepers Association (SGA), Scottish Land and Estates (SLE), Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), Scottish Raptor Study Groups (SRSG), Science and Advice for Scottish Agriculture (SASA), National Wildlife Crime Unit (NWCU), British Association for Shooting and Conservation (BASC) and the Scottish police.

Here it is, and we have added a few comments at the end:

COLLECTION OF EVIDENCE PROTOCOL FOR INCIDENTS OF RAPTOR CRIME

1. Introduction

1.1 Police have a duty to investigate crime and all Forces have a single point of contact with regard to wildlife offences. Each Force also has a number of Wildlife Crime officers specially trained to deal with offences against raptors in a manner consistent with legal prosecution procedure. This includes knowledge regarding relevant legislation, power to enter and search land, authority to seize evidence, requirements for corroboration, safeguarding chains of evidence and forensic capabilities. Consequently, all crime or suspicious activity relating to raptor persecution should be reported to the Police.

1.2 Such incidents could include reports of dead or dying birds, egg stealing, nest interference and disturbance, raptors caught in traps or devices set to catch them, suspected poisoned baits, incidents involving commercial operations and suspicious activity.

1.3 As crimes against raptors can occur in remote countryside, all investigations are risk-assessed by Police with regard to health and safety implications.

1.4 The specific legislation covering matters to do with raptor crime (including their nests) is the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 (as amended).

1.5 This protocol is intended for all groups and members of the public who are not authorised by statute to conduct criminal investigation into offences against raptors.

1.6 If evidence of suspected raptor persecution is found by members of the public, the protocol outlined below should be followed. Occasions may arise when the public decide to choose between preserving a crime scene in accordance with prosecution procedures, and interference for the sake of human or animal welfare, or for reasons of urgency. Consideration should always be taken with regard to all risks posed by equipment, live species or carcasses. Any interference with a legitimate operation may result in prosecution. Consequently, the protocol outlined below has been recognised as the recommended method of evidence recovery with regard to raptor crime.

2. Protocol

2.1. Incidents of raptor crime are often found by members of the public. Those which, on the basis of the information available, are suspected of being a crime, must be reported to the police. Any evidence should be neither handled nor interfered with at this stage.

2.2 Any crime that is in progress or has just been committed, or where the suspect(s) is still in the vicinity, the Police should be contacted (if possible) using ‘999’ and the caller should be guided by the operator. In all other cases where facilities allow, the caller should immediately contact their respective Police Force call centre, ask if possible to speak with a wildlife crime officer, and provide them with the following information:

- Explain what has been seen or found and why crime is suspected.

- Provide an estimate of how long the bird has been dead if a carcass is found.

- Give descriptions of any suspects and vehicles seen.

- Give a GPS reading or a grid reference of the crime spot (if possible).

- Provide reasons if suspecting the presence of pesticides.

- Divulge any other potential risk hazards.

- Give any key landmarks to assist Police in finding the location at a later time.

- Note if there are power lines overhead or any obvious sign of how the bird died.

- Give any details known of the estate, farm, owner or employees

The caller will then be guided by the Police as to what steps to take.

2.3 If the caller is unable to contact the Police immediately or has to leave the location, the caller should follow the course of action outlined below:

Carcasses

In the event of finding a carcass in an area easily accessible to Police, to:

- Record the grid reference.

- Photograph the carcass and any other item that might appear to be obvious evidence (if possible).

- Leave the carcass where found.

- If the carcass looks like a bait, where possible cover it over with available branches or vegetation to lessen the risk of predation.

- Report it to the nearest Police Station.

In the event of finding a carcase in a remote area, to:

- Record the grid reference.

- Recover the carcass only if suitably equipped and deliver it to the nearest Police Station, or

- Photograph the evidence (if possible), cover it over with available branches or vegetation to lessen the risk of predation and report it to the nearest Police Station.

Injured Birds

In the event of finding a live, injured raptor suspected to have been the victim of crime:

- Record the grid reference.

- Moving the bird is entirely at the risk and assessment of the finder.

- Contact the Police at the earliest opportunity to arrange further specialist veterinary assistance.

Traps

In the event of finding an unlawful trap:

- Record the grid reference.

- Make the trap inoperative only if safe to do so and if sure that it has not been lawfully set, otherwise do not interfere with it and report it to the nearest Police Station.

Nest Disturbance

In the event of finding physical nest disturbance in an area accessible to Police:

- Record the grid reference.

- Photograph any carcass and/or other item that might appear to be obvious evidence (if possible).

- Leave the carcass and/or items where found.

- Report it to the nearest Police Station

In the event of any physical nest disturbance in a remote area:

- Record the grid reference.

- Photograph the nest and any other item that might appear to be obvious evidence (if possible) and report it to the nearest Police Station.

- Recover any item that may appear to be obvious evidence only if corroborated and able to do so without destroying or contaminating fingerprints/DNA, and deliver it to the nearest Police Station.

Shooting

In the event of finding a shot raptor:

- Ensure one’s own safety.

- If a dead bird is found, follow the procedure for ‘Carcasses’ if safe to do so.

- If the bird is still alive, follow the procedure for ‘Injured Birds’ if safe to do so.

2.4 The police will follow up reports of suspected wildlife crime, including a scenes-of -crime examination if appropriate, within a time-scale appropriate to the effective investigation of the type of incident.

2.5 If a suitable response to an incident by the police is not possible within the time-scale needed for effective investigation, the police may make specific requests of the member of the public and that, if relevant, the crime scene is preserved until a scenes-of-crime examination can be carried out.

2.6 All efforts must be made to preserve evidence in a manner compatible with the standards required for admissibility as evidence in court by following the principles within this protocol.

2.7 Where there is evidence of an offence, costs of any necessary examinations will be met by the police.

2.8 Any subsequent media release should be in accordance with existing protocols and must not compromise any subsequent Police investigation.

2.9 Some agencies have specific powers enacted by law to collect evidence under prescribed circumstances. Those powers remain unaffected by this protocol but the organisations concerned are bound by alternative working arrangements with the Scottish Police.

It’s interesting that the protocol emphasises (in bold) that suspected raptor crimes should be reported to the police. It’s also noticeable that the protocol does not include the additional reporting of suspected raptor crime to the RSPB. Whilst the police have a statutory duty to investigate wildlife crime, we all know too well that some forces are better at this than others. Even former Environment Minister Roseanna Cunningham acknowledged as much (see here). If another agency (e.g. RSPB) has also been informed about the suspected incident, then increased pressure can be applied to ensure the police do actually investigate the incident. The RSPB has a track record of doing this (e.g. see here), but if the suspected incident is only reported to the police, then who will check whether the incident has been investigated? This protocol does not provide for any follow-up procedures.

Not only that, in a recent report by the National Wildlife Crime Unit (Strategic Assessment, February 2011; see NWCU 2011_02 strategic-assessment), the following statement appears in the section about recent peregrine persecution:

“Almost half of these reports originated from the RSPB but were not reported by the police force the offence occurred in“. (Page 30, paragraph 6.12).

So again, if a suspected raptor persecution incident is only reported to the police, and that particular police force then fails to report the incident to the NWCU, then the NWCU’s annual figures on raptor persecution incidents will be flawed.

Thanks to the contributor who brought this document to our attention.

Well finally, the National Gamekeepers’ Organisation has responded to one of the many emails we know were sent to them asking whether convicted gamekeeper Glenn Brown was one of their members (see here).

Well finally, the National Gamekeepers’ Organisation has responded to one of the many emails we know were sent to them asking whether convicted gamekeeper Glenn Brown was one of their members (see here).

In the November 2011 edition of Birdwatch magazine, Mark Avery calls for our views about hen harriers and grouse moors. He says that if we send our views to the Birdwatch editor, they’ll be summarised and sent to a range of organisations including the Moorland Association, the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust, the RSPB and the Scottish Raptor Study Groups.

In the November 2011 edition of Birdwatch magazine, Mark Avery calls for our views about hen harriers and grouse moors. He says that if we send our views to the Birdwatch editor, they’ll be summarised and sent to a range of organisations including the Moorland Association, the Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust, the RSPB and the Scottish Raptor Study Groups. Is it just us, or is anyone else curious about the deafening silence of landowner and gamekeeper organisations following last week’s report about the discovery of poisoned bait on Glenlochy Estate (see

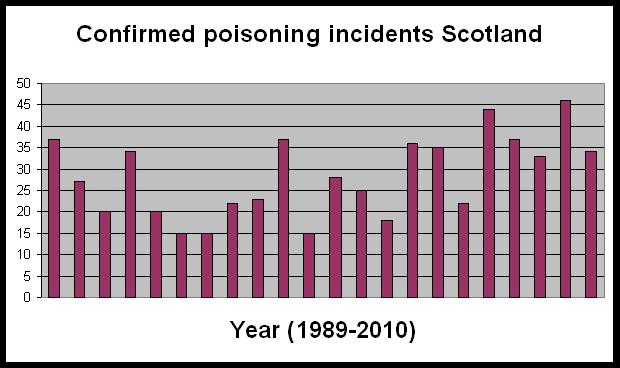

Is it just us, or is anyone else curious about the deafening silence of landowner and gamekeeper organisations following last week’s report about the discovery of poisoned bait on Glenlochy Estate (see  If you look closely at the graph, you will see a great deal of variation between years in the number of confirmed poisoning incidents. Of particular interest are the years 1994 and 1995 – in these two years, confirmed poisoning incidents dropped to a low of 15 from a previous high of 35+. However, if you then look at the following three years, the number of confirmed incidents steadily rose until they reached 35+ again. In 1999, the figure dropped again to 15, and from then until 2010, that figure has steadily risen and fallen, although never reaching the low of 15 again. So what does that tell us? I’m fairly sure that in the years 1994 and 1995, the game shooting lobby would have declared a ‘victory’ as the figures had dropped so much, and would have shouted from the hilltops that they’d changed their ways. I’m also fairly sure that in the following three years when the figures rose again, the conservationists would have declared a ‘victory’ and pronounced that their claims of widespread persecution had been vindicated. Either way, it is clear that neither ‘side’ can draw conclusions just based on an annual figure; for a trend to be detected, we need to see long-term figures.

If you look closely at the graph, you will see a great deal of variation between years in the number of confirmed poisoning incidents. Of particular interest are the years 1994 and 1995 – in these two years, confirmed poisoning incidents dropped to a low of 15 from a previous high of 35+. However, if you then look at the following three years, the number of confirmed incidents steadily rose until they reached 35+ again. In 1999, the figure dropped again to 15, and from then until 2010, that figure has steadily risen and fallen, although never reaching the low of 15 again. So what does that tell us? I’m fairly sure that in the years 1994 and 1995, the game shooting lobby would have declared a ‘victory’ as the figures had dropped so much, and would have shouted from the hilltops that they’d changed their ways. I’m also fairly sure that in the following three years when the figures rose again, the conservationists would have declared a ‘victory’ and pronounced that their claims of widespread persecution had been vindicated. Either way, it is clear that neither ‘side’ can draw conclusions just based on an annual figure; for a trend to be detected, we need to see long-term figures.