Regular blog readers will know that I’ve been trying to uncover the reasoning and process behind NatureScot’s sudden decision last autumn to change its approach and amend the brand new grouse moor licences that had been issued to sporting estates in Scotland under the new Wildlife Management & Muirburn (Scotland) Act 2024.

The changes made by NatureScot significantly weakened the licence by changing the extent of the licensable area from covering an entire estate to just the parts of the estate where red grouse are ‘taken or killed’, which on a driven grouse moor could effectively just mean a small area around a line of grouse butts.

NatureScot also added a new licence condition that it claimed would allow a licence revocation if raptor persecution crimes took place outside of the licensable area, but many of us believe this to be virtually unenforceable.

This new condition also means that all the other offences listed in the Wildlife Management & Muirburn Act that are supposed to trigger a licence revocation (i.e. offences on the Protection of Badgers Act 1992, Wild Mammals (Protection) Act 1996, Conservation (Natural Habitats etc) Regulations 1994, Animal Health & Welfare (Scotland) Act 2006, Hunting with Dogs (Scotland) Act 2023) are NOT covered by the new licence condition. The new condition ONLY applies to raptor persecution offences (see previous blogs here, here, here, here, and here for background details).

As I blogged on 18 December 2024, NatureScot was clearly playing for time by stalling on releasing overdue FoI documents that I had asked for to try to find out what was behind the complete mess grouse shoot licensing has become.

Finally, on 19 December 2024, by sheer coincidence, I’m sure, NatureScot provided a response, amounting to 162 pages of internal and external email correspondence between July and October 2024, relating specifically to the changes made to grouse licence conditions.

Here is the cover letter sent to me by NatureScot, explaining what information was being released and what was being withheld

And here is the substantial correspondence that NatureScot had with representatives of the grouse shooting industry prior to NatureScot making changes to the licence:

It’s a lot to take in, and as you can imagine, it’s taken a while for me and my colleagues to digest the contents. To be frank, there’s nothing in the material released that we didn’t know or suspect had probably gone on, but the detail is very enlightening.

It’s very clear that the level of engagement between NatureScot and Scottish Land and Estates (SLE, the lobby organisation for grouse moor owners in Scotland) was truly staggering. SLE (and latterly, BASC) were granted at least eight exclusive meetings with NatureScot staff between 15 July and early October to discuss the grouse licensing issue, without a word to any other stakeholders that this issue was being discussed.

No notes of these meetings, or any of the many phone calls between SLE and BASC and NatureScot staff, has been provided in the FoI response.

Also missing from the FoI response is the legal advice that NatureScot received about making changes to the grouse licence, despite it being clearly critical to NatureScot’s decision making.

However, on the back of that legal advice, it is clear that SLE and BASC were given exclusive previews by NatureScot of proposed changes to the licence to agree before they were implemented.

From the perspective of those of us who campaigned long and hard for a robust system of grouse moor licensing, and engaged diligently with the process of the Wildlife Management Bill as it progressed through Parliament and the subsequent meetings to determine the accompanying codes of practice, I’m not sure how this fits into NatureScot’s oft-repeated claim to seek “openness and transparency”.

The policy intent of the legislation, part of the Wildlife Management and Muirburn Act, which was overwhelmingly passed by the Scottish Parliament, was crystal clear – “to address the on-going issue of wildlife crime, and in particular the persecution of raptors, on managed grouse moors. It will do this by enabling a licence to be modified, suspended or revoked, where there is robust evidence of raptor persecution or another relevant wildlife crime related to grouse moor management such as the unlicenced killing of a wild mammal, or the unlawful use of a trap”.

Given the amount of evidence that SLE was invited to give during the Committee stages of the Bill’s progression, including representations by their legal representative, one wonders why SLE didn’t question the interpretation of the draft legislation defining land to be covered by a licence at that stage?

SLE certainly raised questions and objections about many other aspects of the legislation during that process but maybe didn’t want the kind of public debate in front of MSPs that raising this issue at that time would have led to?

Instead, the land management sector, and in particular SLE, pursued an extraordinary level of behind-the-scenes access to NatureScot staff after the legislation had been agreed through the democratic process, who in turn bent over backwards to accommodate all their demands, simply to head off the threat of legal action over interpretation of the new grouse licensing legislation, specifically how much of an estate should be covered by a licence.

At this point, it’s legitimate to question SLE’s motives for trying to limit the amount of an estate that is licensed. Surely, if an estate’s employees aren’t committing wildlife crime, the extent of the licence shouldn’t actually matter?

Anyway, it’s clear that discussions with SLE about a “legal issue” began in early July 2024, shortly after the period for grouse shooting applications had opened. It’s also apparent that shooting representative organisations were already advising their members via social media to delay submitting applications until the issue that “relates to the area of land to which the licence relates” was resolved.

The FoI documents show that RSPB picked up on this and emailed NatureScot on 18 July 2024 asking for details. The response from NatureScot, sent the following day, appears to be reassuring, stating:

“We are clear that licences we issue should relate to the full landholding and not just land over which grouse are taken and killed, because as you well know, raptor persecution undertaken in connection with grouse moor management could take place anywhere on a property, not just on the grouse moor itself”.

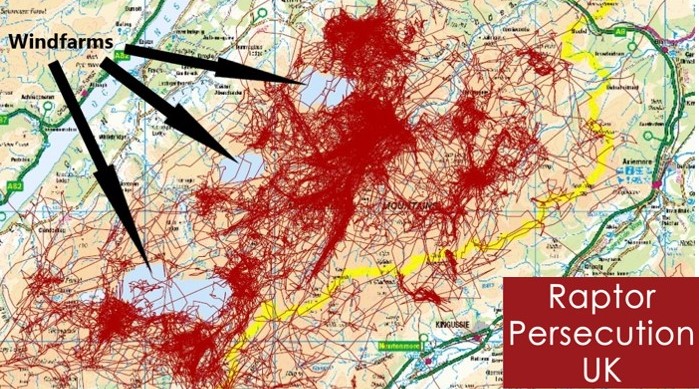

I, and I’m sure most readers of this blog, completely agree with this sentiment. We all know of many, many cases of raptors killed by gamekeepers on grouse shooting estates in places well away from where actual grouse shooting occurs – in woodlands, at nests on crags, in adjoining farmland. I don’t doubt that the majority of MSPs who passed the legislation would also have shared this view. Indeed, why would anyone who genuinely wishes to see raptor persecution addressed not agree?

However, we now know that NatureScot went from saying they were comfortable that the process in place was robust (on 16 July) to bending over backwards to accommodate every suggestion SLE made about new conditions, despite recognising early on that the “policy intent” of the Wildlife Management and Muirburn Act might not be realised if areas covered by licences were too small.

Interestingly, the document also shows that NatureScot’s internally-agreed line of communications (from 19 July 2024) would be that they were “working closely with stakeholders to develop a workable licensing scheme for grouse shooting that supports those who manage their grouse moors within the law and acts as a strong deterrent to raptor persecution”.

Really? This has proven to be completely misleading and disingenuous at best. In reality it’s clear that the only organisations NatureScot was working closely with were SLE and BASC, even giving them advance notice of proposed new licence conditions for their comments and approval.

In contrast, there is no correspondence with the police or NWCU to ask their opinion on the proposed new conditions and their enforceability, or any hint of wider discussion or consultation with any other organisation, despite other’s involvement in giving evidence to Parliament or contributing to the Grouse Code of Practice.

Instead, there has been a concerted effort to placate representatives from the industry responsible for the illegal slaughter of huge numbers of raptors and other protected species, resulting in a significant number of investigations and prosecutions, just to head off legal threats. The rest of the world only became aware of these changes to the licences when it was all cut and dried, a done deal, published on NatureSot’s website.

As I have written before, not only is the area to be covered by a licence down to the whims of the licence applicant, whatever the non-legally binding expectations of the licensing authority that it would include the whole grouse moor, but a new condition that I and many others believe to be unenforceable has been added.

A stinging, but apparently unanswered, email sent from the RSPB to NatureScot on 10 October 2024 sums it up:

“This new ‘wildlife crime licensing condition’ will apply outside of the licensed area of a landholding but only where offences committed are related to management of the grouse moor. In a scenario where a buzzard is found dying in an illegally-set pole trap on a sporting estate, 2km away from the licensed grouse moor, we question what evidence will be required, and how it will be obtained, to allow an assessment if that crime was linked to grouse moor management, particularly if it was an estate that also had pheasant shooting?

“In summary, we believe that this new condition means that establishing a link between raptor persecution offences and grouse moor management, and to act as a meaningful deterrent to wildlife crimes, will now require a burden of proof that will be virtually impossible to achieve”.

So much for these licences being a deterrent to raptor persecution! We also now know that NatureScot didn’t undertake a single measure of compliance monitoring or checks on the use of the 250 licences it issued for the 2024 grouse shooting season (see here).

It’s becoming increasingly apparent that a culture of appeasement to the land management sector has become embedded in NatureScot. I’ll have a lot more to say about this over the coming weeks, (there is an ongoing related issue that has so many similarities but I can’t write about it yet, pending legal advice) but there is a growing sense of unease amongst conservationists with regard to decisions being taken by an organisation that should be leading on protecting Scotland’s wildlife.

In the meantime, concerned blog readers may feel moved to write (politely) to the Scottish Government’s Minister for Agriculture & Connectivity, Jim Fairlie MSP, (email: MinisterforAC@gov.scot) to ask him what he intends to do to fix the huge loophole that NatureScot has created in the first Bill he led on in Government.

I’ll be very interested in the responses you get.

You might also increasingly be thinking that licensing grouse shooting just isn’t going to work, and the whole thing should just be banned. If so, please sign this petition.