Press release from Cairngorms National Park Authority (24 November 2025)

PEREGRINE NUMBERS IN DECLINE IN CAIRNGORMS NATIONAL PARK

The last UK-wide survey of peregrines took place in 2014 and covered Scotland as a whole, showing a 9% decline in numbers across the country. The Scottish Raptor Monitoring Scheme also found some evidence of a decline from 2009-18; however, no survey was undertaken to assess peregrine populations specifically within the National Park during that time.

In 2024 the Cairngorms National Park Authority collaborated with three of the regional branches of the Scottish Raptor Study Group: Highland, North East of Scotland and Tayside and Fife, to carry out a survey to establish how many peregrine sites within the National Park were occupied and assess their breeding success.

Raptor Study Groups have records going back to the 1960s of sites where peregrines have bred within the Cairngorms National Park and these were used as the basis for the survey. The study shows that the estimated number of peregrine pairs in the breeding season within the National Park has declined by 56% since 2002, with less than half of territorial pairs successfully fledging young in 2024.

Contributing factors are likely to include upland land management practices, decreased prey availability for peregrines, wildlife crime and, more recently, outbreaks of Avian Flu.

It is a complex picture, and more research is needed to understand the key factors and gain a better understand of upland raptor population dynamics – including interspecific competition (ie competition for resources between individuals of different species) and the influence of prey availability. It will require action from the Park Authority working with a range of partners, including the Raptor Study Groups, NGOs and estates on the ground, as well as NatureScot and other public bodies, to explore what can be done to try and turn the tide for peregrine and all raptors in the National Park.

Dr Sarah Henshall, Head of Conservation at the Cairngorms National Park Authority, said: “This is the first time we have been able to get a clear view of peregrine falcon numbers in the National Park and it paints a bleak picture. We will be working closely with Raptor Study Groups, estates and other experts to explore a range of options such as the installation of nest cameras to help us understand bird behaviour, DNA work to support wildlife crime prevention initiatives and GPS tagging to get information on bird movements and survival.

“Our ongoing conservation work, from ecological restoration to increasing the sustainability of moorland management, aims to benefit habitats for peregrine and other key upland species. This survey further highlights the importance of this work and strengthens our resolve to help this iconic bird thrive.”

ENDS

The report can be read / downloaded here:

My commentary:

The continued decline of Peregrines in the Cairngorms National Park comes as no surprise whatsoever, and its link to intensively-managed driven grouse moors even less so.

The illegal persecution of Peregrines on driven grouse moors is an issue that has been documented repeatedly in scientific papers since the early 1990s, nationally (e.g. see here) and regionally (e.g. see here for research from northern England). A particularly illuminating paper published in 2015 reported specifically on the decline of breeding Peregrines on grouse moors in North-East Scotland, including those on the eastern side of the Cairngorms National Park (here).

This latest report from the Cairngorms National Park Authority, based on fieldwork undertaken by the Scottish Raptor Study Group, is a welcome addition to the literature and will help inform the new requirement (under the Wildlife Management & Muirburn Act 2024) to monitor and report every five years on the status of a number of raptor species (Peregrine, Golden Eagle, Hen Harrier & Merlin) on grouse moors in Scotland as a measure of how well / badly the legislation is working.

The report’s findings are cautious, citing a number of factors that could be potential drivers influencing the recent decline (e.g. Bird Flu, interspecific competition etc) but these cannot, and do not, account for the long-term decline of Peregrines in the uplands, either within the Cairngorms National Park or in other upland areas. I’m pleased to see the report acknowledge this.

Let’s not kid ourselves. The Cairngorms National Park Authority has known for some time that illegal raptor persecution is a huge issue within the Park boundary – check out what the CNPA was proposing in 2013 to tackle the problem (see here) – unsurprisingly, it didn’t work.

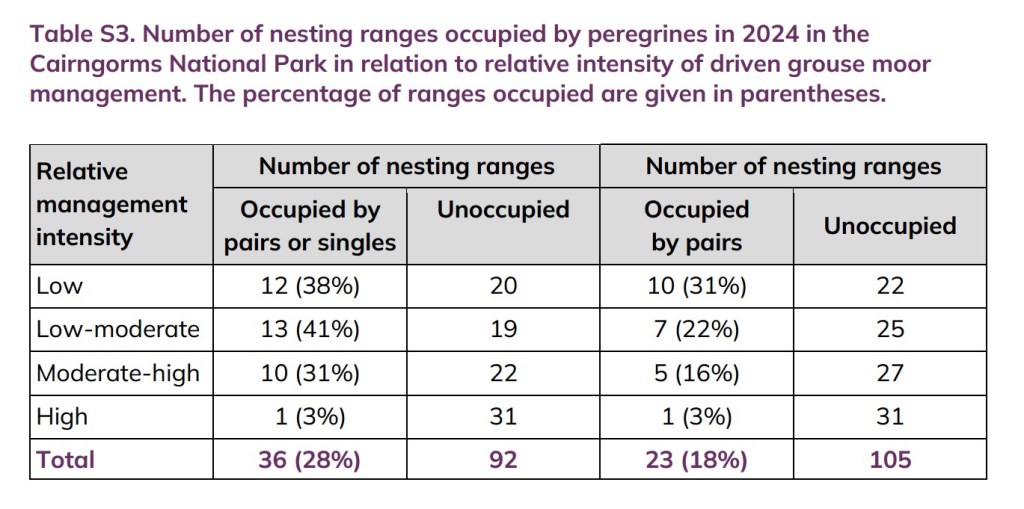

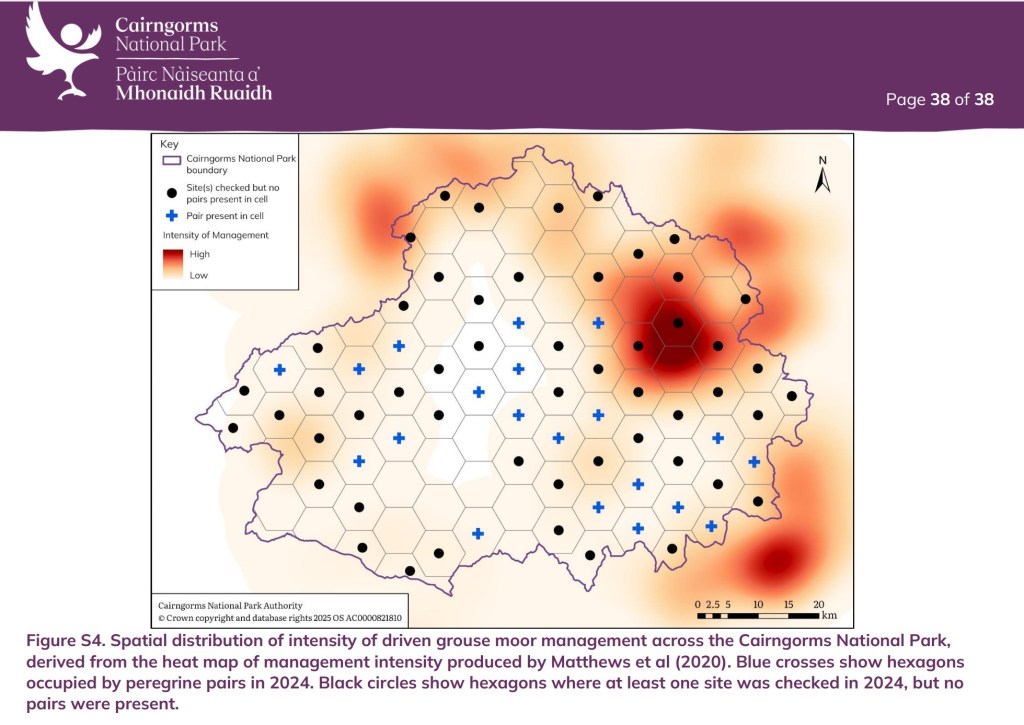

The latest report includes an analysis of the relationship between Peregrine breeding site occupancy and the intensity of grouse moor management (ranging from ‘low’ to ‘high’ management intensity and everything in between).

The results speak for themselves:

I’m slightly confused by table S3. As I understand it there are a number of ‘nesting ranges’ within the study area and these can be (a) occupied by a pair, (b) occupied by a single bird or (c) unoccupied. I understood the first data column to include ranges occupied by either a pair or a single (a + b) and the third data column to include ranges occupied by pairs (a only) but it is unclear why the number of unoccupied ranges then differs between data columns 2 (92 unoccupied ranges) and 4 (105 unoccupied ranges). I am probably being dumb and missing something obvious but I would appreciate it if someone could explain what. That said, I agree that there is a clear and marked effect of grouse moor management intensity on range occupancy.

I suspect that the difference is the number of ranges occupied by single birds. In the Yorkshire Dales most Peregrine sites on grouse moors have been unoccupied by breeding pairs for nearly 25 years, some longer than that. However some sites are when checked occupied by single birds ( in my limited experience) these birds are almost always male. I once had it explained to me by a now retired keeper thus: “Peregrines often occupy traditional sites during February, sometimes even earlier. When that is the case you go on a filthy mid week evening and we all know to shoot the bigger one” If you do this often enough the situation at such sites goes from properly occupied to occupied by an adult male and an immature female who is unlikely to breed. Then just a male as almost all females are removed from the local population to unoccupied. Thus to my mind in most cases sites occupied by single birds are sites that will soon be unoccupied. Sad but to me clear evidence of persecution and to my mind long passed time when the authorities should recognise this as clear evidence and start action under the options available to them in Scotland but sadly not England. I suspect that an analogous situation pertains to traditional Eagle territories on such estates too.

As I’ve said above raptor workers have long known how this works and what this data means. It needs to be made clear to those in power, in order to get something done about it. It was clear in the northern England study by Amar et al, that once you move away from grouse moors even in the same general areas Peregrine occupation increased as did breeding success and on those rare occasions when birds were unhampered on grouse moors brood sizes were comparable strongly indicating it was NOT a prey problem.

“As I understand it there are a number of ‘nesting ranges’ within the study area and these can be (a) occupied by a pair, (b) occupied by a single bird or (c) unoccupied.”

Correct.

“I understood the first data column to include ranges occupied by either a pair or a single (a + b) and the third data column to include ranges occupied by pairs (a only)”

Correct.

” but it is unclear why the number of unoccupied ranges then differs between data columns 2 (92 unoccupied ranges) and 4 (105 unoccupied ranges)”

‘Unoccupied’ does not mean the same in both cases.

In the first case (column 2) ‘unoccupied’ really means unoccupied, because a nest can have either one or a pair of birds, so the number of ranges without any birds (nests) at all really means they are ‘unoccupied’.

But in the second case, ‘unoccupied’ is a poor choice of description, because what they mean are the number of ranges without a pair of birds nesting (therefore, some of these so-called ‘unoccupied’ ranges actually have a nest, but with just the one bird)

If you look at the data, the total number of ranges within each management category is always 32, while the total number of ranges overall is always 128, and the columns add up.

What they are trying to show in the data is how the level of management intensity correlates more closely with a drop-off in the number of paired birds nesting across each area, but a bit less so if you include nests with just single birds.

Is the peregrine the species that is most “effectively” persecuted on grouse moors? I would say so.

What I mean is – in persecution terms in total numbers the buzzard is undoubtedly top of list, by miles. And in terms of a species population being most vulnerable to effects of persecution, it is the hen harrier, is it not? But in terms of the almost complete “successful” cancelling out as a breeding bird on grouse moors, it must surely be the peregrine. Too visible, too noisy, too easily attracted, too easy to shoot when nesting and roosting in & around regular places.

But then again, the Eagles take a hammering in that part of Scotland too, so maybe they are jointly top of that sorry league table.