The following is a guest blog by someone who wishes to remain anonymous, although I know their identity.

STOBO HOPE – NATURESCOT REFUSES LICENCE APPLICATION BY PRYOR & RICKETT SILVICLUTURE TO HUNT FOXES WITH 19 DOGS

Many of you may have read about Stobo Hope in the Scottish Borders, with government body Scottish Forestry awarding a contract worth £2 million of taxpayers’ money to the Guernsey-registered Forestry Carbon Sequestration Fund, managed by True North Real Asset Partners Ltd with CEO Harry Humble (see here), to plant a giant Sitka spruce plantation.

Stobo Hope appears to be another questionable forestry project approved by Scottish Forestry – the excellent Parkswatch Scotland blog has exposed many, one of the latest being Muckrach (see here and here).

A crowdfunder campaign by the Stobo Residents Action Group, with support from Wild Justice, Raptor Persecution UK and Parkswatch readers, helped raise nearly £30,000 for a judicial review. The decision by Scottish Forestry to approve the plantation without an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) was challenged (see here).

Many people are grateful for your support in opposing this scheme, which seems to typify destruction of valuable upland habitats in Scotland. The judicial review was successful, with the Scottish Government eventually conceding before going to court – cancelling the £2 million contract, grant of consent and all associated funding (see here). The forestry work has apparently been halted by a court order since early September 2024 and Scottish Forestry have stated they will decide again if an EIA is needed (see here). [Ed: update, since this guest blog was written, news has emerged that the investment company behind the development work at Stobo Hope has lodged its own legal challenge against Scottish Forestry’s decision to halt all groundwork – see here].

Were dubious claims by Scottish Forestry about black grouse intended to help avoid an EIA?

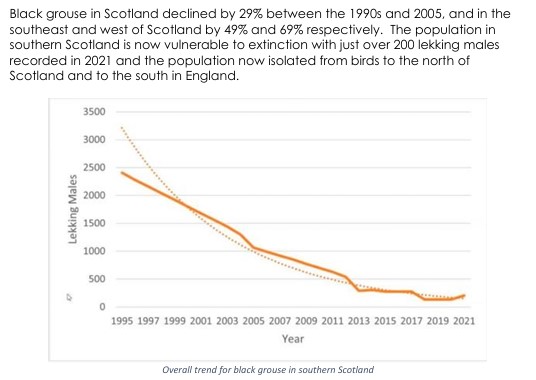

After decades of claiming intensive grouse shooting is beneficial for the local economy and wildlife, some landowners and managers are now claiming to be ‘mitigating climate change’ by planting Sitka spruce. Instead of having a mixture of open moorland with some native woodland, where grouse, waders, raptors and other wildlife can co-exist, moorlands across the Southern Uplands and elsewhere are being destroyed by conifer plantations in the wrong place. This is reaching the point that black grouse are now facing extinction in the Southern Uplands, as explained in a report by the Southern Upland Partnership (see here).

Following advice on 9 January 2024 from Mabbett and Associates Ltd, now called Arthian Ltd (see here), the ecological consultancy engaged and paid for by forestry agents Pryor and Rickett Silviculture to undertake the ecological surveys for Stobo, Scottish Forestry decided on 18 January 2024 that ‘this project is not likely to cause a significant negative effect to black grouse’, helping avoid an EIA.

This begs the question of whether Scottish Forestry employ their own ecologists to review and check such claims in applicants’ reports or do they just take these claims as read? Mabbett claimed ‘that whilst the scheme will have localised ecological impacts, it will not have a significant impact on the features identified withing [sic] previous habitat and ornithological surveys’:

Research has shown black grouse require several hundred of hectares of contiguous moorland habitat at a minimum for breeding. Due to the sedentary nature of black grouse, their breeding areas need to be close to other suitable moorlands for viable populations. Stobo and neighbouring woodland creation schemes, if approved, would together amount to losing nearly ten square kilometres of moorland.

Scottish Forestry claimed that there would be 246.4 ha of open ground within 1.5km of the lek as part of several so-called mitigation measures. Scottish Forestry failed to explain most of these open areas were fragments of relatively unsuitable habitat on exposed hilltops and ridgelines (with deer fences) further away from the lek and there would be 463.6 ha of trees replacing the areas of suitable habitat, so there is no longer any contiguous moorland.

Scottish Forestry stated that ‘the applicant has provided a Predator Control Management Plan to target particular species which could adversely impact upon black grouse’.

Scottish Forestry ignored the RSPB’s earlier prediction in September 2023 that the Stobo lek would become extinct:

In addition to all the damage on site by the forestry managers from groundworks, drains, forest tracks and planting Sitka spruce, herbicide was applied across vast areas of heather moorland in August 2023, five months before a contract was approved by Scottish Forestry (see here), who claimed they didn’t notice this herbicide damage for a whole year.

The Stobo Residents Action Group explained that this herbicide would have ‘wiped out important plant communities including heather, blaeberry and many species of wildflowers, grasses, ferns, lichens and mosses’ thus ‘destroying the food supply for mammals, birds, reptiles and invertebrates including the red-listed black grouse’. It is understood up to 400 hectares could have been sprayed with herbicide.

Pryor and Rickett Silviculture applied to NatureScot for a licence to hunt foxes at Stobo with 19 dogs

Many readers may be aware that the new Hunting with Dogs (Scotland) Act 2023 (see here) prohibits fox hunting with more than two dogs without a licence. This legislation was intended to close loopholes in the now repealed Protection of Wild Mammals (Scotland) Act 2002, which effectively allowed fox hunting to continue for sporting purposes.

NatureScot has authority to grant licences for hunting with more than two dogs under certain ‘exceptions’; (i) the management of wild mammals above ground and (ii) environmental benefit (see here). Campaigners have argued that this new licensing system still has loopholes, allowing fox hunting to continue under these ‘exceptions’ (see here and here).

A FoI from NatureScot has revealed that forestry agents Pryor and Rickett Silviculture Ltd (see here) applied to NatureScot for a licence in March 2024 to use 19 foxhounds to hunt foxes for ‘environmental benefit’ at Stobo. It was claimed this would help protect black grouse from predation from foxes as part of its ‘Predator Control Management Plan’ also targeting corvids and stoats, using Larsen and Perdix spring traps.

The applicant claimed that black grouse were ‘present across the site, with multiple areas identified as Lek’s [sic] and Breeding sites’ (but is unclear what constitutes ‘breeding sites’), also claiming ‘the site is also understood to be a significant movement corridor for Black Grouse between neighbouring glens’:

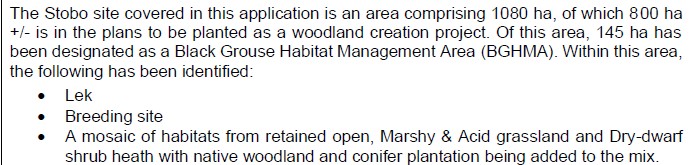

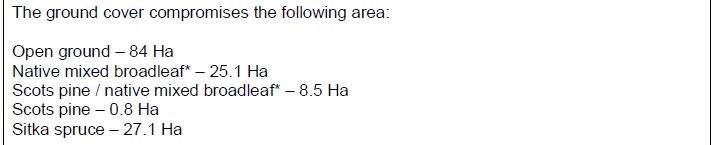

It was claimed management proposals ‘have been designed to increase the quality of the habitat available for black grouse within the site’. However, it claims that of the 1080 ha Stobo site ‘800 ha +/- is in the plans to be planted as a woodland creation project’ with a ‘Black Grouse Habitat Management Area’ of 145 hectares, of which just 84 hectares is open ground:

The applicants claimed to be ‘partnering with the University of Edinburgh to establish a long-term study of the black grouse management area’:

This claim was also made in the Stobo Woodland Creation Operational Plan submitted to Scottish Forestry by Pryor and Rickett Silviculture on behalf of True North Real Asset Partners Ltd:

A FoI response from the University of Edinburgh contradicted this claim, stating they had ‘not been engaged to put in place long-term research on black grouse’. True North Real Asset Partners Ltd had approached the University for discussions but no research collaboration resulted.

Did the applicants approach Edinburgh Napier University as an alternative organisation for a research study as the applicants also made several references to Edinburgh Napier University?

A FoI response from Edinburgh Napier University explained there were no plans for Edinburgh Napier University researchers using Stobo as a long-term research site:

Applicants attempt to justify reasons for licence application

NatureScot require applicants to justify the proposed number of guns and dogs. Five guns and nineteen dogs were proposed, with the applicant claiming if only two dogs were allowed the ‘guns’ (people with the guns) would become ‘very cold and bored and unwilling to partake in future fox control work’:

NatureScot also asks applicants to demonstrate all alternative options to achieving the licensable purpose, explaining that applicants cannot use the presence of ‘dense cover’ to justify the use of dogs. The applicant appears to rule out alternatives such as cage traps, diversionary feeding and fencing, claiming it was unsafe to increase the number of guns ‘without the use of a pack of dogs’:

The ‘high level of ground cover’ mentioned sounds rather like ‘dense cover’. The picture of a spruce plantation below gives an idea of the ‘high level of ground cover’ or ‘dense cover’ that would occur in the long-term, which also hardly looks like suitable black grouse habitat.

Reasons for refusal of the licence application by NatureScot

A licence can only be granted if NatureScot considers three tests have been met; (i) Licensable purpose, (ii) No alternative solutions to achieve purpose, and (iii) Contribution to long-term environmental benefit.

The first test was passed as NatureScot were satisfied there was a purpose in controlling foxes, potentially reducing black grouse predation. The second test was not passed as the applicants had not fully demonstrated that there were no alternative solutions to controlling the fox population without increasing dog numbers. The third test was also not passed as NatureScot were not satisfied a long-term environmental benefit would be achieved:

Criticisms by NatureScot

NatureScot said that the loss, fragmentation and deterioration of suitable habitats in the uplands from commercial forests was leading to a decline in black grouse. NatureScot stated the proposed mitigation measure in the plan ‘to plant commercial plantations with edges of mixed broadleaves will still unlikely sufficiently limit the impacts of the planting of the large conifer plantations on the open moorland that black grouse prefer’.

NatureScot quoted the applicants (who had given reasons for declines in black grouse to justify predator control), stating ‘Black grouse like the ground cover in young plantations, but as these develop into solid conifer thickets they tend to leave’. The loss of suitable habitat for black grouse and absence of ‘a wider-scale and longer-term environmental plan for addressing black grouse conservation’ under the proposed scheme was mentioned. NatureScot explained that the applicant ‘had not provided sufficient detail or explanation to demonstrate how the activity will be monitored and therefore how it will achieve long-term or significant environmental benefit’.

NatureScot also questioned why it was not possible to use two dogs to flush foxes to waiting guns.

The scale of the commercial plantations at Stobo

For the Stobo plantation, of the planted area, 72% is Sitka spruce, with a further 10% of commercial Scots pine and Douglas fir, so commercial coniferous forestry amounts to 82% of the planted area. The map below does not show three new plantations to the north, west, south or a proposed plantation to the east, creating a giant spruce plantation across what was previously contiguous moorland. Nearly ten square kilometres could be cumulatively planted, affecting fourteen square kilometres:

Why did the application fail to declare if the dog handler didn’t have wildlife crime convictions?

Although the completed licence application stated ‘no’ in response to a question asking if the applicant or anyone working under the licence being applied for had been ‘convicted of a wildlife crime or disqualified from keeping dogs’, when the same question was put for the dog handler (whose details were redacted), this was unanswered. Perhaps this was missed out by accident or the applicant was uncertain about the background of the dog handler?

‘Greenwashing’ to try and create a loophole in foxhunting legislation?

After reading this licence application, one cannot help thinking that the applicants were trying to take advantage of current black grouse presence to have fox hunting with nineteen foxhounds for sporting purposes. At the time of writing, no licences for hunting with more than two dogs for ‘environmental benefit’ have been granted anywhere – only for preventing serious damage to livestock, woodland or crops (see here).

A FoI response from July 2024 showed that of eight licence applications for the ‘environmental benefit’ option, seven were refused and one was frozen, pending further information, suggesting that NatureScot are restricting applicants from exploiting possible loopholes in the new legislation.

Are Scottish Forestry ignoring ecological impacts of new woodlands becoming sporting estates?

It is understood many organisations involved with conservation of golden eagles, black grouse and other projects in the Southern Uplands may be reluctant to publicly object to, or criticise forestry proposals because this could jeopardise future funding from the Scottish Government and Scottish Forestry.

It appears Scottish Forestry are exploiting those lack of objections, to help avoid EIAs. Scottish Forestry have also been publicly funding new woodland creation schemes that subsequently become overrun with released pheasants, red-legged partridges and even mallard ducks for recreational shooting, with significant negative ecological impacts (see here), even in Scotland’s so-called National Parks as explained on Parkswatch (see here).

These game bird releases have multiple detrimental impacts, such as on native woodland vegetation and remaining open areas of grassland. This occurs through factors such as eutrophication of soil, losing herb rich vegetation and birds eating invertebrates and even reptiles.

Scottish Forestry do not appear to account for the significant negative future environmental impacts of intensive recreational game shooting in their assessment of woodland grant scheme applications. It would be interesting if the Stobo scheme was being considered for future game shooting by the landowners and managers, in addition to its now foiled plans for foxhunting.

Scottish Forestry have said that they will ‘now screen the project again’, to see if an EIA is required, taking into account ‘all other new relevant information’ (see here).

Will Scottish Forestry again be selective in choosing information and sources, continuing to incorrectly maintain ‘this project is not likely to cause a significant negative effect to black grouse’?

Will Scottish Forestry continue to align its claims with those of True North Real Asset Partners Ltd, whose CEO Harry Humble asserted in the Scotsman (see here) that ‘the scheme has been designed specifically to favour black grouse, with an enhanced mix of species and open space provision in line with best practice derived from decades of research’.

Will Scottish Forestry continue to disregard warnings by reputable ecologists and the RSPB that the black grouse lek at Stobo will disappear, with NatureScot confirming black grouse ‘tend to leave’ (plantations of the kind at Stobo), as corroborated by peer-reviewed research?

ENDS