A new paper has just been published in the latest edition of British Birds (March 2017) detailing a 30-year study of breeding merlins on four grouse shooting estates in the Lammermuir Hills in south east Scotland:

A new paper has just been published in the latest edition of British Birds (March 2017) detailing a 30-year study of breeding merlins on four grouse shooting estates in the Lammermuir Hills in south east Scotland:

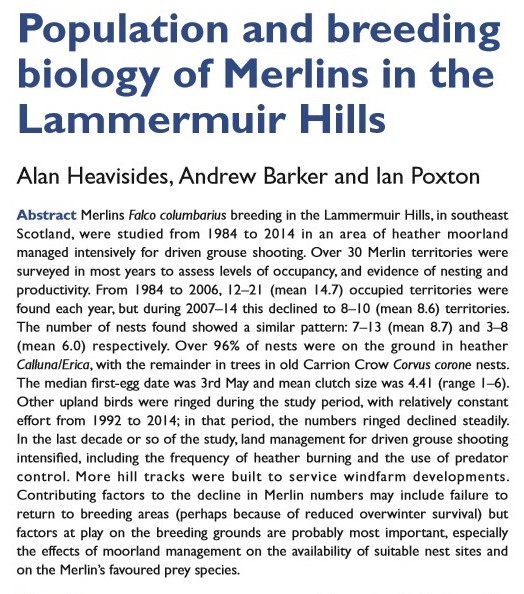

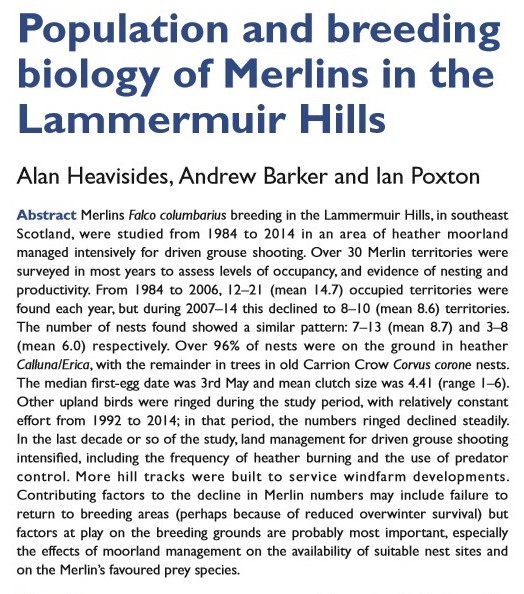

Heavisides, A., Barker, A. and Poxton, I. (2017). Population and breeding biology of merlins in the Lammermuir Hills. British Birds 110: 138-154.

The authors are long time members of Lothian & Borders Raptor Study Group and this paper is the latest in a series of peer-reviewed scientific papers written by Scottish Raptor Study Group members reporting on the detrimental effects of intensive grouse moor management on several raptor populations. Other recent publications have included the catastrophic decline of hen harriers on NE Scotland grouse moors, here and the long-term decline of peregrines in the uplands of NE Scotland, here.

The results of the Lammermuir merlin study suggest that illegal persecution is NOT thought to be a contributing factor in this population’s decline. Merlins are generally tolerated on UK grouse moors (presumably as they’re not a big threat to red grouse) and the grouse shooting industry will often use the merlin’s breeding success on grouse moors to counter any accusation that raptors (in general) are illegally killed there. Obviously, that argument doesn’t stand up to scrutiny.

What is suggested in this paper is that an intensification of grouse moor management in the Lammermuirs over the last ten years has probably had an impact on this merlin population, particularly an increase in the heather burning regime.

It’s also interesting to note the authors’ records of other breeding raptor species in the Lammermuirs:

Only three hen harrier broods were found throughout the study period, the last in 1994.

There were at least three sites where peregrines attempted to breed in the early years of the study, the last successful one being in 1994.

Buzzards are commonly seen in the Lammermuirs but only nest on the periphery of the study area, “probably because all of the suitable trees that were used previously have now been removed”.

Short-eared owl sightings were “quite frequent” in the early study years and nests were “occasionally found”, but “these casual observations declined as the years went by and became unusual during the later years”.

Unfortunately we’re not allowed to publish the full paper here (you’ll either have to subscribe to the British Birds journal or contact one of the authors and ask for a copy for personal use). We can, though, publish the abstract. Here it is:

This long-term study was brought to an abrupt end after the 2014 breeding season. This is touched on in the paper but has been more elaborately described during recent conference presentations by one of the authors. The authors mention they enjoyed good cooperation from landowners and gamekeepers during the early study years, and were granted permission to drive their vehicles on estate roads to help access some of the more remote nest sites. However, in 2015, when the researchers contacted the estates to let them know that fieldwork was about to begin, two of the four estates told them they were no longer welcome and withdrew permission for vehicular access.

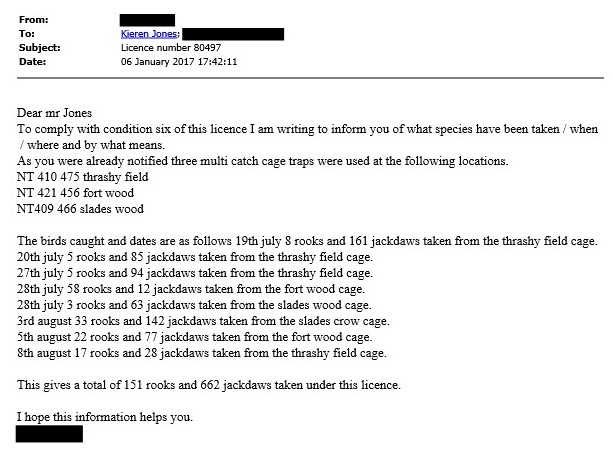

The authors believe this was a reaction to criticism made directly by the study team of various aspects of the estates’ grouse moor management techniques, particularly the increased use of bridge (rail) traps that were catching / killing non-target species such as dippers, merlin and ring ouzels. The authors also speculated that it may have been a more ‘general backlash’ following recent widespread criticism of driven grouse moor management across the UK.

Whatever the reason was, it flies in the face of the Scottish Moorland Group’s recent claim to the Scottish Parliament’s Environment Committee that grouse moor owners, “Would very much like to see greater cooperation between ourselves, the Raptor Study Groups, and the RSPB” (see here).

Really? Funny way of showing it.

The two estates in question are reported to be the Roxburghe Estate and the Hopes Estate. It’s fascinating to see the Hopes Estate involved in all this.

The Hopes Estate is owned by Robbie Douglas Miller, who also happens to run the Wildlife Estates Scotland (WES) scheme, administered by Scottish Land & Estates, as a way of showcasing the, ahem, fabulous work that estates undertake to protect wildlife. We’ve recently blogged about one of these accredited WES estates – the Newlands Estate where gamekeeper Billy Dick was convicted of throwing rocks at, and stamping on, a buzzard (see here).

In 2014 the Hopes Estate gained accreditation to the WES scheme – independently verified, of course. Estates that are awarded accreditation have to meet certain criteria, including:

- Commitment to best practice

- Adoption of game and wildlife management plans that underpin best practice

- Maintaining species and habitats records

- Conservation and collaborative work

- Integration with other land management activities (such as farming, forestry and tourism)

- Social, economic and cultural aspects (such as employment, community engagement and communications)

Hmm.

A new paper has just been published in the latest edition of British Birds (March 2017) detailing a 30-year study of breeding merlins on four grouse shooting estates in the Lammermuir Hills in south east Scotland:

A new paper has just been published in the latest edition of British Birds (March 2017) detailing a 30-year study of breeding merlins on four grouse shooting estates in the Lammermuir Hills in south east Scotland:

Last week, Environment Cabinet Secretary Roseanna Cunningham gave a speech at the Scottish Raptor Study Group’s annual conference, where she described, with feeling, her ‘contempt‘ for the continued illegal persecution of birds of prey (see

Last week, Environment Cabinet Secretary Roseanna Cunningham gave a speech at the Scottish Raptor Study Group’s annual conference, where she described, with feeling, her ‘contempt‘ for the continued illegal persecution of birds of prey (see  About eighteen months ago in October 2015 we wrote a blog about the use of medicated grit to dose red grouse with a parasitic wormer drug called Flubendazole.

About eighteen months ago in October 2015 we wrote a blog about the use of medicated grit to dose red grouse with a parasitic wormer drug called Flubendazole.

Scottish Greens MSP Andy Wightman has tabled a parliamentary motion calling on the Scottish Government to increase the investigatory powers of the SSPCA.

Scottish Greens MSP Andy Wightman has tabled a parliamentary motion calling on the Scottish Government to increase the investigatory powers of the SSPCA.